The Colors of the Countryside: A Review of the First National Farmers’ Painting Exhibition and Thoughts on Collecting

- OGP

- Oct 5, 2025

- 6 min read

By OGP Reporters / Members Contribute File Photos

Oh Good Party

This exhibition, with its structured narrative, cross-regional samples, and strong engagement, reintroduced “farmers’ painting” from regional folk aesthetics into the context of “contemporary folk art.” It is an iconography of land and people, a visual archive of social memory and communal emotion. For art lovers, it is a highly suitable collectible—broadening perspective, deepening cultural understanding, and enriching aesthetic experience. But as an investment asset, it is less ideal. Therefore, the recommendation is to pursue “research-based/thematic collecting” as the main line, placing aesthetics, culture, and long-term companionship above profit.

The exhibited works present a strong “rustic flavor,” a distinctive “regional character,” and an intense “spirit of the times.” They reflect how numerous farmers’ painting creators and grassroots art groups perceive life with their hearts, recording the new scenes of rural production and life in the new era through unique perspectives and vivid, simple artistic language. Together, they demonstrate the vigorous vitality of Chinese rural painting creation.

I. Exhibition Review

On June 27, the “First National Farmers’ Painting Exhibition” opened at the China Art Museum, with both the ground floor and B2 floor serving as interconnected exhibition areas. The exhibition will run until August 24. Over 5,000 works were submitted nationwide, of which 544 were selected for display. Several monumental collaborative works from “painting towns” were also specially presented. The curatorial structure was divided into four chapters—“Cultivation / Harvest / Celebration / Renewal”—forming a clear narrative and regional framework. Official data show that in its 51 open days, the exhibition received nearly 550,000 visitors, hosted over a hundred public education events, and achieved significant public engagement and social attention.

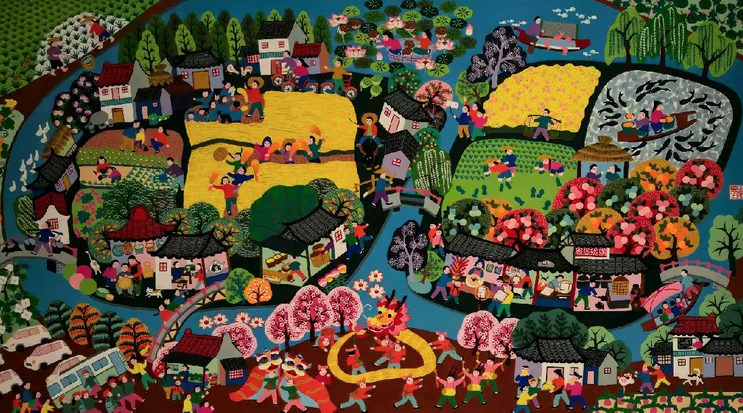

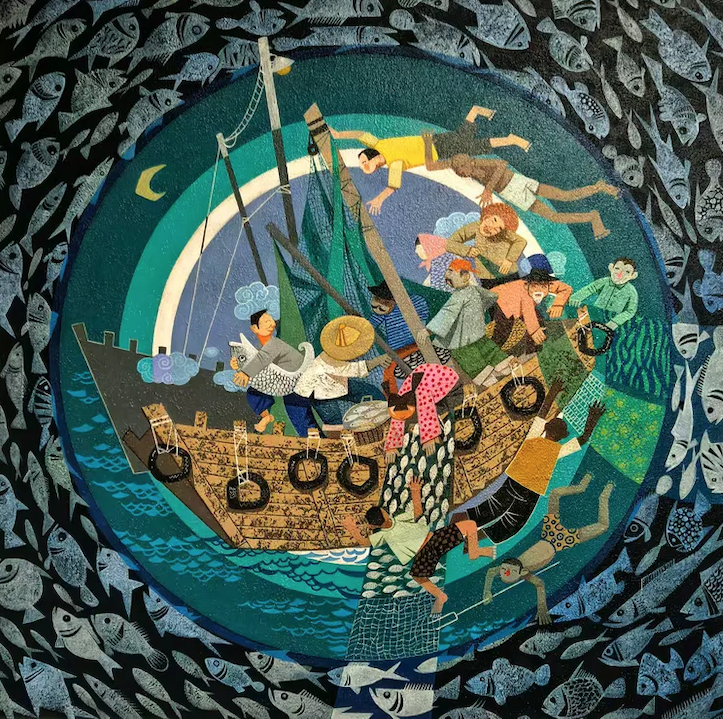

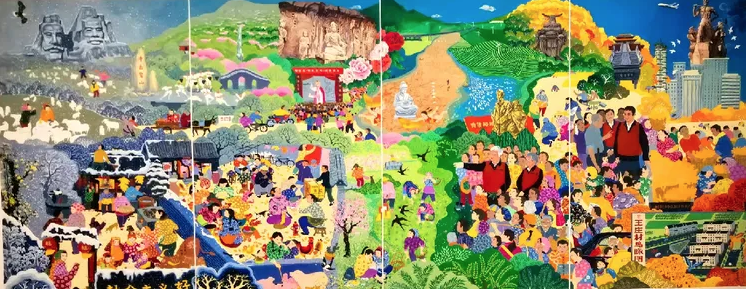

At the venue, many “painting towns” made their collective appearances: for example, the specially invited large-scale piece Harmony in Diversity from Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County in Guangxi, which, through vibrant colors and group structures, portrayed the symbiotic landscape of the “colorful Dong homeland”; the Guangdong team’s collaborative Tides of South Guangdong (350×250 cm) unfolded across sea bays, ports, and factory zones, showcasing the region’s industry and urban vibrancy; Shanghai artist Chen Huifang’s Shanghai School Jiangnan—New Yuan Embankment Farming Scroll (350×200 cm) employed a “Jiangnan agricultural scroll” with scattered perspective, combining Shanghai aesthetics with pastoral memory; Henan’s Ancient Rhyme, New Melody juxtaposed traditional instruments and market scenes to reflect the daily rhythms of the Central Plains’ “ancient echoes and new voices.”

II. Extending the Typology of Farmers’ Painting

What it is—A style/type, not a limitation of “who the author is.”

“Farmers’ painting” first emerged in the 1950s–60s within rural cultural and collective creative practices, drawing inspiration from paper cutting, embroidery, New Year prints, and temple paintings. Over time, it developed a distinct language characterized by planar compositions, exaggeration and distortion, strong coloration, multiple scattered viewpoints, and narrative group scenes. In contemporary times, the creative community has expanded beyond the traditional “farmer artist + art instructor” model to include teachers, artisans, designers, returning youths, and more. Thus, “farmers’ painting” is better understood as a style of contemporary folk painting rooted in regional culture.

History and regional lineage.

Scholars generally identify Hu County (now Huyi), Shaanxi, and Jinshan, Shanghai, as key origins and paradigms: Hu County farmers’ painting, which began in 1958, is marked by simplicity, bold colors, and narrative depictions of everyday life. Jinshan, after absorbing Hu County’s experience and Jiangnan’s craft traditions, formed in the 1970s–80s a style blending Shanghai aesthetics with Jiangnan folk imagery. Other places, such as Boli, Jiangsu, also gradually developed local schools in the 1980s.

Sociality and ethnicity.

Farmers’ painting often relies on the community networks of “painting towns” and public cultural spaces. Collective creation, master-apprentice transmission, and local festivals or agricultural practices serve as its foundation, making it a “pictorial chronicle” of regional customs, farming techniques, and rural-urban transitions. This rooted “ethnic–regional” expression has become a cultural emblem of localities, as well as an important intangible cultural heritage and cultural tourism resource.

Value and emotion.

Its value is first and foremost socio-cultural: it translates the wisdom of “acquaintance society,” its ritual structures, and its emotional communities into visual narratives that can be collectively shared. At the same time, its experimentation with color and composition brings both immediate visual pleasure and decorative appeal. Most importantly, “farmers’ painting is only a form—it is not limited to being painted by ‘farmers.’ Artistic value never depends on the creator’s occupation.” Respecting diverse artistic forms is key to understanding contemporary Chinese folk painting.

Selected Works

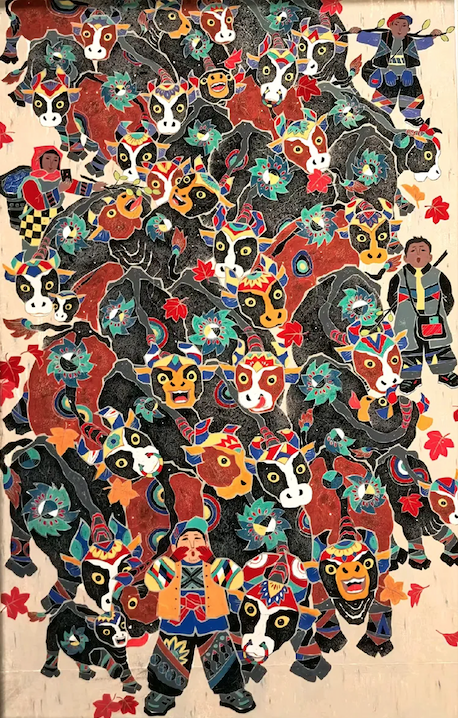

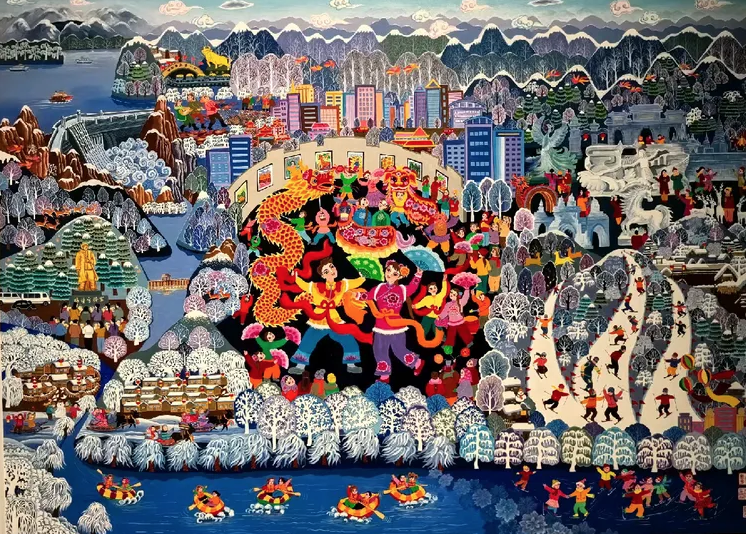

Harmony in Diversity (Guangxi)

A group scene of festivals and labor, using high-saturation colors, dense patterns, and layered “grassland–terrace–crowd” structures to present the Dong community’s sense of shared life and harmony.

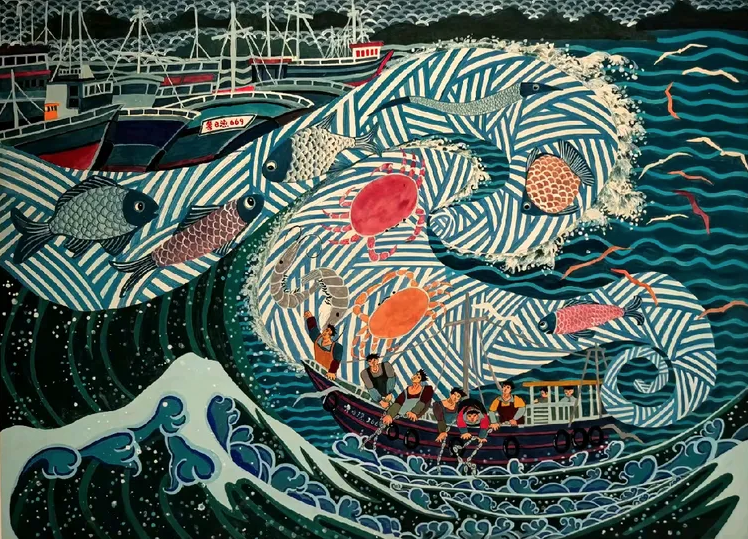

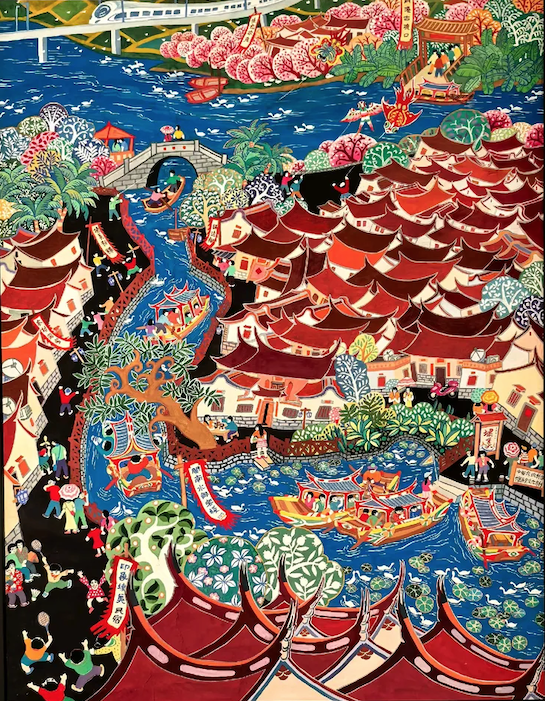

Tides of South Guangdong (Guangdong, 350×250 cm, by Zhong Yonglian, Liang Caihuan, Luo Xuefang, Su Xiaoming)

Its curved bay and skyline generate momentum, while factory, market, and harbor scenes resonate, forming a “lyrical industrial” folk expression.

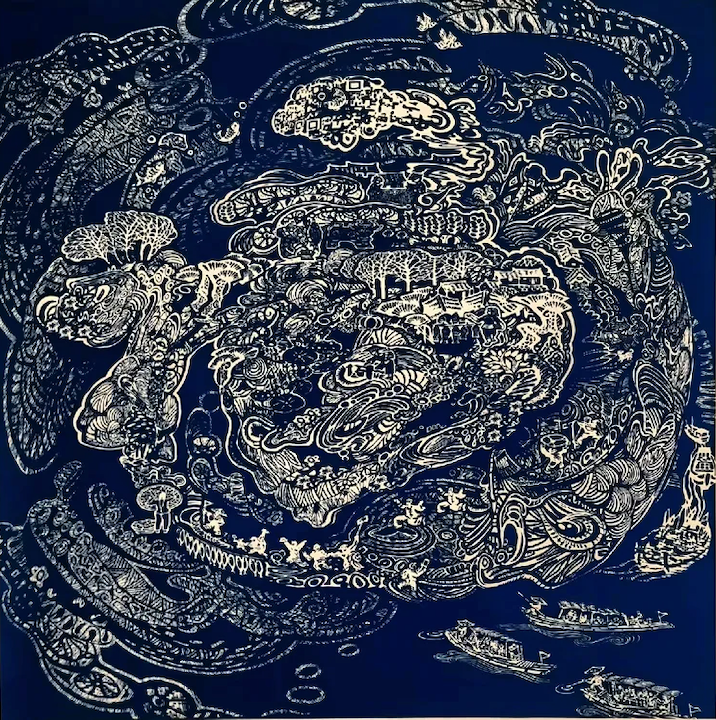

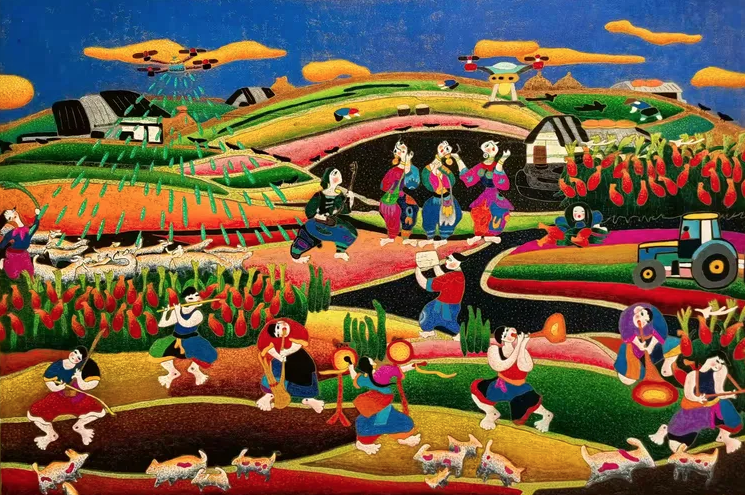

Shanghai School Jiangnan—New Yuan Embankment Farming Scroll (Shanghai, by Chen Huifang)

A scroll-style scattered perspective links farming processes; the vivid Shanghai coloring and Jiangnan’s intricate motifs harmonize, presenting an interplay between city and countryside.

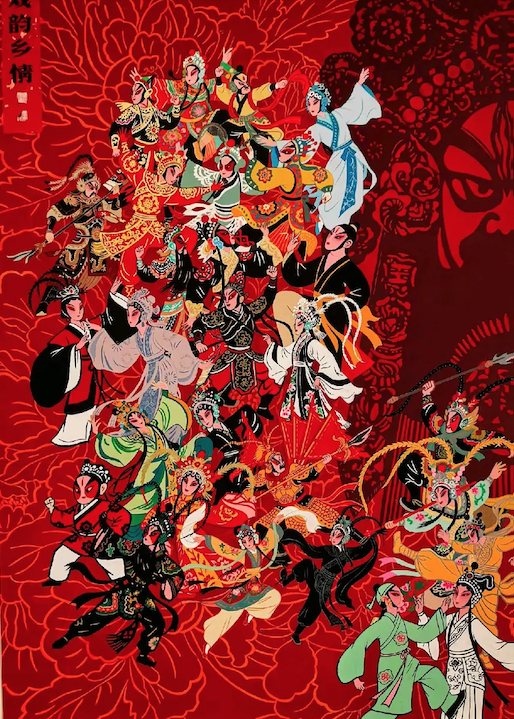

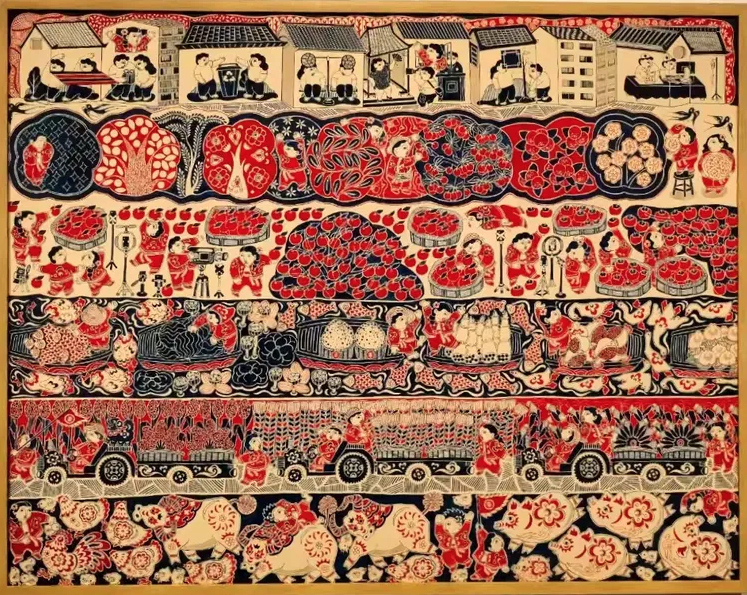

Ancient Rhyme, New Melody (Henan, by Zhou Songxiao, Zhang Xinliang, et al.)

Musical instruments, opera, and market vignettes structure the axis, forming a narrative collage of “ancient and modern juxtaposed.”

III. Artistic Value and Collecting/Investment Advice

A. Artistic Value and Potential

Academic value

As a major category of “modern folk painting,” farmers’ painting holds stable value in visual anthropology, folklore, and visual culture studies. A younger generation of creators is pushing subject matter and language toward contemporary themes (urban nostalgia, migration, industrial landscapes), expanding the scope of academic discourse.

Aesthetic value

Strong coloration, large-scale flat painting, and decorative composition make it well-suited for public spaces and home decoration alike. Group scenes and storytelling reduce “viewing cost” and enhance communicability.

Cultural value

It is a “visual oral history” of rural life, carrying transmissible, researchable, and communicable socio-cultural significance. For institutions and public spaces, it offers strong potential in public education.

Potential value

With new creators joining, farmers’ painting has expanded beyond farming and festivals to include e-commerce, industry, and urbanization as new symbols. It carries the potential for a “traditional vocabulary—contemporary expression” synthesis. For collectors, collecting such works means not only artistic ownership but also cultural recognition and historical preservation.

What kind of collectors are they suitable for?

Academic collectors who value cultural background and research frameworks

Private collectors who appreciate vibrant color and need spatial adaptability

Public institutions, corporate art museums, and folk museums with cultural display needs

B. Investment Attributes: Advantages vs. Risks

Potential Advantages

Relatively accessible price point

Aside from a few well-known names, most works remain within approachable ranges, making it possible to build themed mini-collections (such as “Ocean/Fishing,” “Jiangnan Farming,” “Dong Festivals”).

Exposure dividends from policy and public attention

Large-scale exhibitions and the branding of “painting towns” enhance recognition, aiding collection and dissemination (as seen in this exhibition’s high popularity and broad reach).

Differentiated value

Outside the mainstream art market, farmers’ painting offers an alternative path of “cultural collecting.”

Main Risks

Limited market liquidity

The secondary market is not very active, with weak price discovery in the short term.

Asymmetric information and provenance

In large-scale collaborations and workshop productions, author attributions, provenance, and conservation vary, requiring stricter documentation and authenticity measures.

Stylistic similarity increases selection cost

Shared family-like traits in subject and style may cause valuation differences and aesthetic fatigue.

Conservation challenges

Common materials include xuan paper, gouache, or acrylics, which require careful management of humidity and light.

Farmers’ painting should not be treated as a “pure investment asset.” A safer path is to “prioritize aesthetic and cultural value, with long-term holding in mind,” building research-themed collections that enhance cultural substance and reduce volatility.

C. Practical Collecting Advice

Prioritize primary sources

Acquire through museums/public programs, official painting town institutions, academic exhibition derivatives, or commissioned works—ensuring authenticity, clear background, and proper attribution. Collaborating with local cultural organizations or intangible heritage centers provides endorsed works.

Documentation and archives

Request or create a “work card”—including creation date, medium and size, artist bio, source materials (sketches, work photos), exhibition/publication records; preserve exhibition labels and catalog pages. For collaborative scrolls, secure clear author lists and ownership statements.

Collection themes

Organize around regional themes (“Jinshan—Jiangnan Farming,” “Lingnan—Ocean and Industry,” “Southwest—Ethnic Festivals”), or methodological themes (group scenes, rituals, music, modern industry) to build “thematic collections.” Formal themes like “large-scale group scenes,” “collaborative scrolls,” or “narrative single works” enhance research and exhibition value.

Focus on new-generation artists and large-scale collaborations

The former bring fresh artistic vocabulary; the latter suit institutional or public display, though collectors must confirm authorship and ownership agreements.

Conservation and display

Xuan paper works should be professionally mounted; keep in cool, dry conditions, away from strong light; regularly check pigment stability, applying protective coatings when necessary. Large-scale works are ideal for institutions/public spaces; private collectors are advised to focus on medium or small sizes.

Future direction

With the advance of rural revitalization and folk art research, farmers’ painting is expected to further enter museum academic systems and cross-disciplinary design fields. Rather than pursuing financial returns, collectors should aim to build academic and systematic collections, which hold greater long-term cultural significance and exhibition potential.

This exhibition, with its structured narrative, cross-regional samples, and strong engagement, reintroduced “farmers’ painting” from regional folk aesthetics into the context of “contemporary folk art.” It is an iconography of land and people, a visual archive of social memory and communal emotion. For art lovers, it is a highly suitable collectible—broadening perspective, deepening cultural understanding, and enriching aesthetic experience. But as an investment asset, it is less ideal. Therefore, the recommendation is to pursue “research-based/thematic collecting” as the main line, placing aesthetics, culture, and long-term companionship above profit.

Comments