The Power of the Private, the Light of Civilization - Reflections on China's Private Collectors and Museums through "Grand View of Heaven and Earth"

- OGP

- Jul 14, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jul 28, 2025

By OGP Reporters / Members Contribute File Photos

Oh Good Party

The "Grand View of Heaven and Earth" exhibition sent a clear message: Chinese private museums are transitioning from mere "showrooms of wealth" to platforms for cultural production and knowledge dissemination. This rise should not be dismissed as "showing off" or "private indulgence." It reflects the formation of a new cultural responsibility community. The stewards of tomorrow's civilization will not be cloistered elites, but collectors, curators, museum operators, and public participants who share resources, research, taste, and knowledge.

In late spring, We had the pleasure of visiting the highly anticipated exhibition "Grand View of Heaven and Earth: Civilizational Imprints Across Time," presented by the Long Museum (West Bund), founded by renowned collectors Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei. Featuring nearly 200 privately held antiquities dating from the Shang and Zhou dynasties to the Ming and Qing periods, the exhibition was divided into four thematic sections. It offered a sweeping civilizational dialogue across 3,000 years of Chinese history and attracted wide attention from the art world, academia, and collector communities.

Crucially, all of the exhibits in this show came from private collections and independent institutions. This not only demonstrated the depth and breadth of China's private collecting world but also provided a compelling example of the cultural potential and societal responsibility of private collectors and museums. The exhibition was more than a visual and intellectual feast; it was a stress test of the capacity of China’s private collecting ecosystem to organize, curate, and integrate cultural resources.

Private Collectors Unite to Create a Landmark Exhibition in the "High-Value Era"

All objects featured in this exhibition originated from private collections and span a wide range of categories, including oracle bones, bronzes, jade artifacts, porcelain, Buddhist sculptures, and classical furniture. Most were publicly displayed for the first time, and many carry extraordinary market value, showcasing the refined taste and deep resources amassed by Chinese private collectors over decades.

Curator Liu Yiqian was candid: "This is a commercial high-value exhibition. It represents the collective achievements of decades of private collecting and reflects the organizational capability and public discourse power of private collectors and institutions outside the national museum system."

Since founding the Long Museum in 2012, Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei have established one of China's most iconic private museums. Their structured and systematic exhibitions span ancient Chinese art, revolutionary art, and modern painting. In this exhibition, they not only presented their own rigorous and expansive holdings but also collaborated with several prominent collectors to weave a cultural tapestry that bridges time and genre—a harbinger of the increasing organization and professionalism of China's private museum and collecting communities.

Echoes of Civilization: A Systematic Presentation of 3,000 Years of Artistic Masterpieces

"Grand View of Heaven and Earth" was divided into four major sections: "Longevity of Metal and Stone," "Vessels Carry the Way," "Pure Thought," and "The Inexhaustible Treasury." Through an object-centered yet philosophical approach, the show traced the spiritual genealogy of Chinese civilization over three millennia. Despite their private provenance, these objects collectively rendered a coherent civilizational narrative, transforming isolated relics into a structural and systematic cultural dialogue.

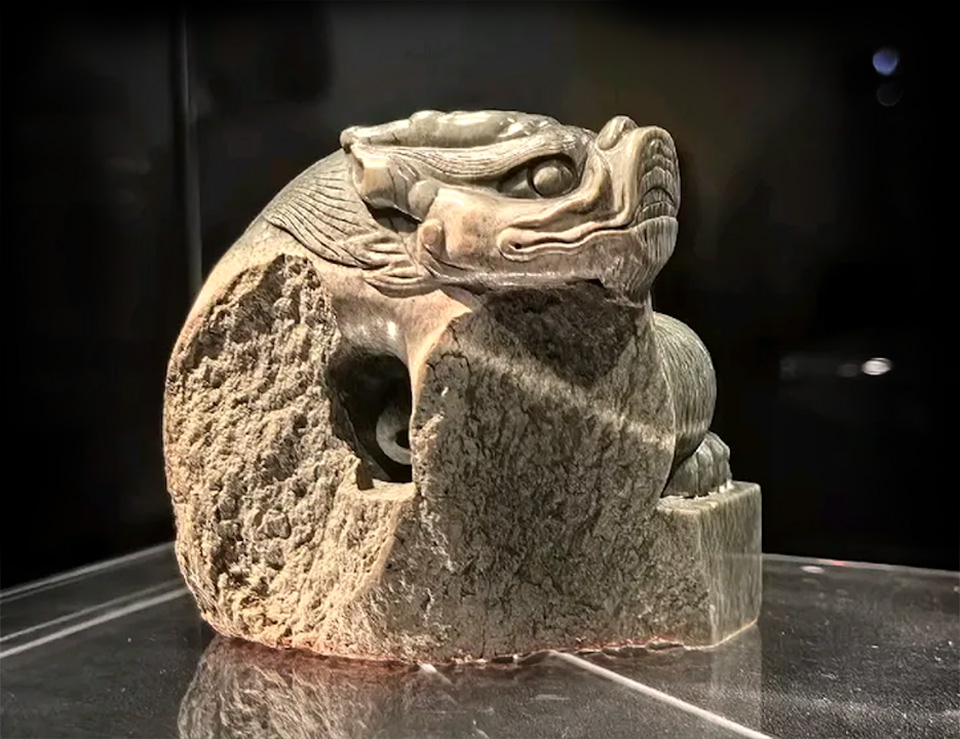

Longevity of Metal and Stone: The Origins of Script, Ritual, and Faith

Oracle bones, bronzes, and ancient jades are the foundational media of ancient Chinese civilization, embodying statecraft, cosmology, and moral ideals. This section presented 34 examples of inscribed oracle bones and 13 sets of rare bronzes, ancient jades, and jade seals—a tangible genealogy of China’s "metal-and-stone spirit."

Oracle bone script, the earliest mature writing system, recorded divination rituals while revealing the political, religious, and social structures of the Shang dynasty. Bronze ritual vessels embodied political hierarchy through their standardized forms and inscriptions documenting enfeoffment, military campaigns, and royal rewards. Jade, from Han-dynasty virtue metaphors to the cultural symbolism of seals, reflected not just material value but aspirational ideals.

Such systematic presentations are rare in private collections, and their inclusion here demonstrated the collectors’ profound understanding of ancient Chinese intellectual history and their long-term commitment to cultural preservation.

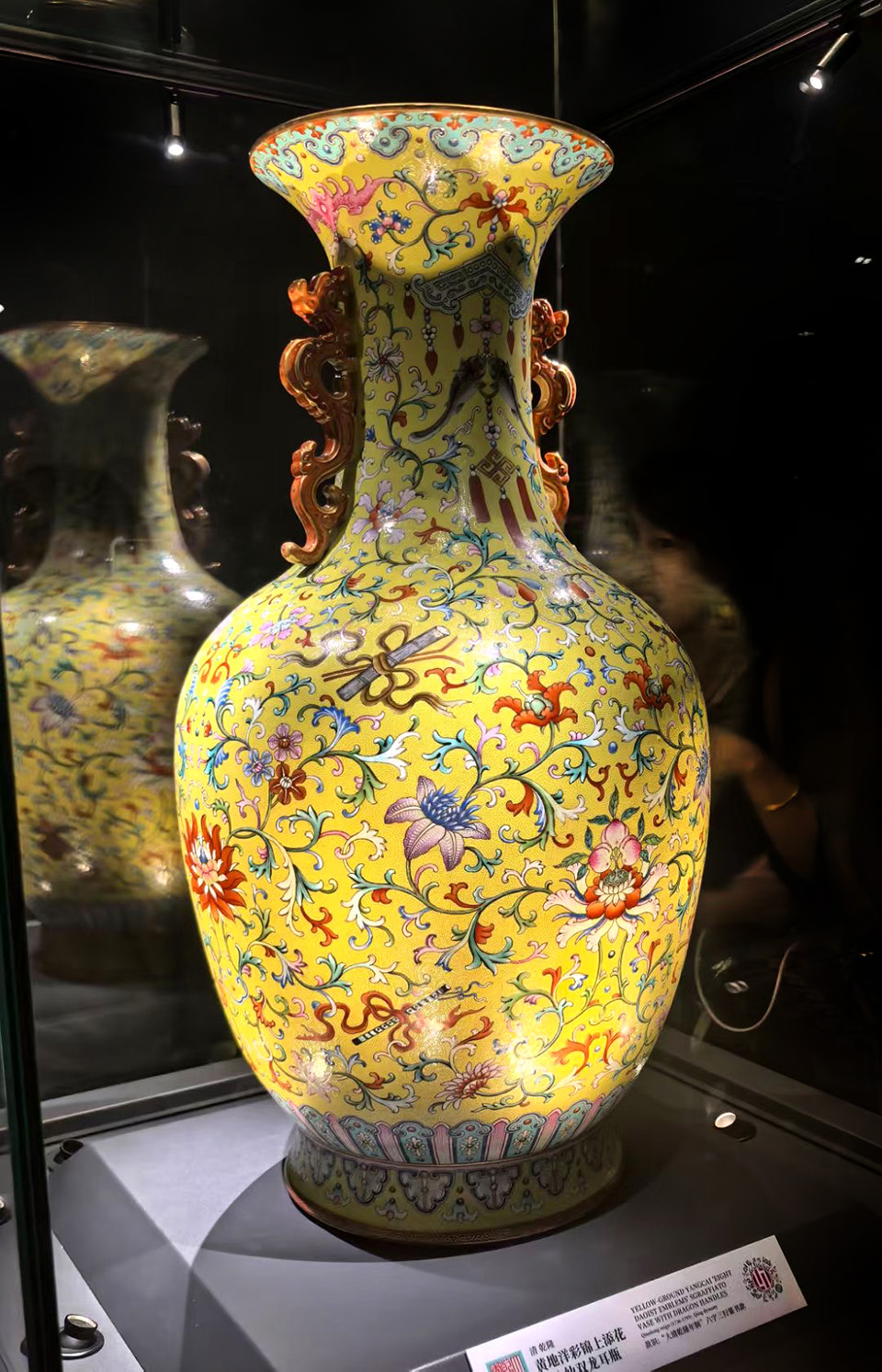

Vessels Carry the Way: Order and Aesthetics in Porcelain

Porcelain is China’s most internationally recognized cultural artifact. This section showcased twelve exemplary pieces from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, illustrating the evolution of aesthetic expression from restrained elegance to exuberant complexity.

From the celestial blue of Ru ware reflecting a “heaven-man unity” worldview, to Southern Song official kilns mimicking bronze ritual vessels, and Yuan blue-and-white porcelain emerging from cross-cultural fusion, these ceramics reveal philosophical depth and technical innovation. The Ming and Qing periods saw the blossoming of overglaze enamel techniques—famille rose, falangcai, and yangcai—that defined global ceramic aesthetics and mirrored late-imperial opulence and cultural anxiety.

Supplied by multiple senior collectors, this section demonstrated not just a quest for rarity, but also an effort to map porcelain’s aesthetic systems and its global cultural significance—hallmarks of the increasing professionalism of private collecting.

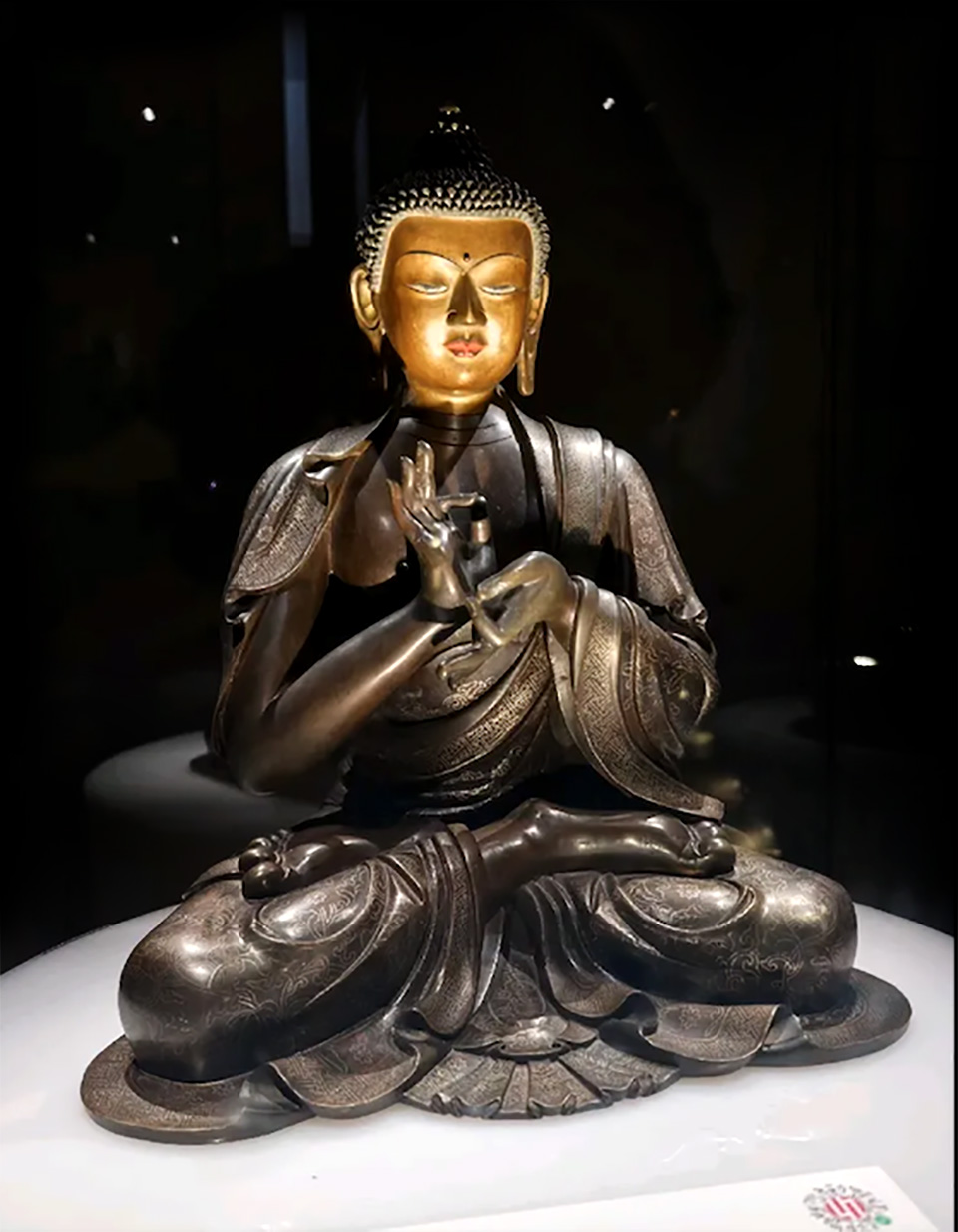

Pure Thought: Faith and Beauty in Religious Iconography

Once a marginal focus in Chinese art history, religious art is now a rising interest among collectors. This section featured eight Buddhist icons and thangkas dating from the 11th century to the Qing dynasty, covering both Tibetan and Han traditions.

Exhibited works included a Yongle-period Vajrabhairava thangka, a Tibetan bronze yogi, and hybrid Han-Tibetan sculptures from the Ming and Qing dynasties. These objects revealed regional interpretations of Buddhist aesthetics and illustrated imperial patronage as a tool of ideological shaping.

Many of these pieces had been privately held for years and were on public view for the first time, highlighting how collectors now actively engage in the research, preservation, and dissemination of religious art. Private collecting is playing a vital role in moving religious art from the periphery into the center of cultural discourse, helping redefine heritage protection as a pluralistic endeavor.

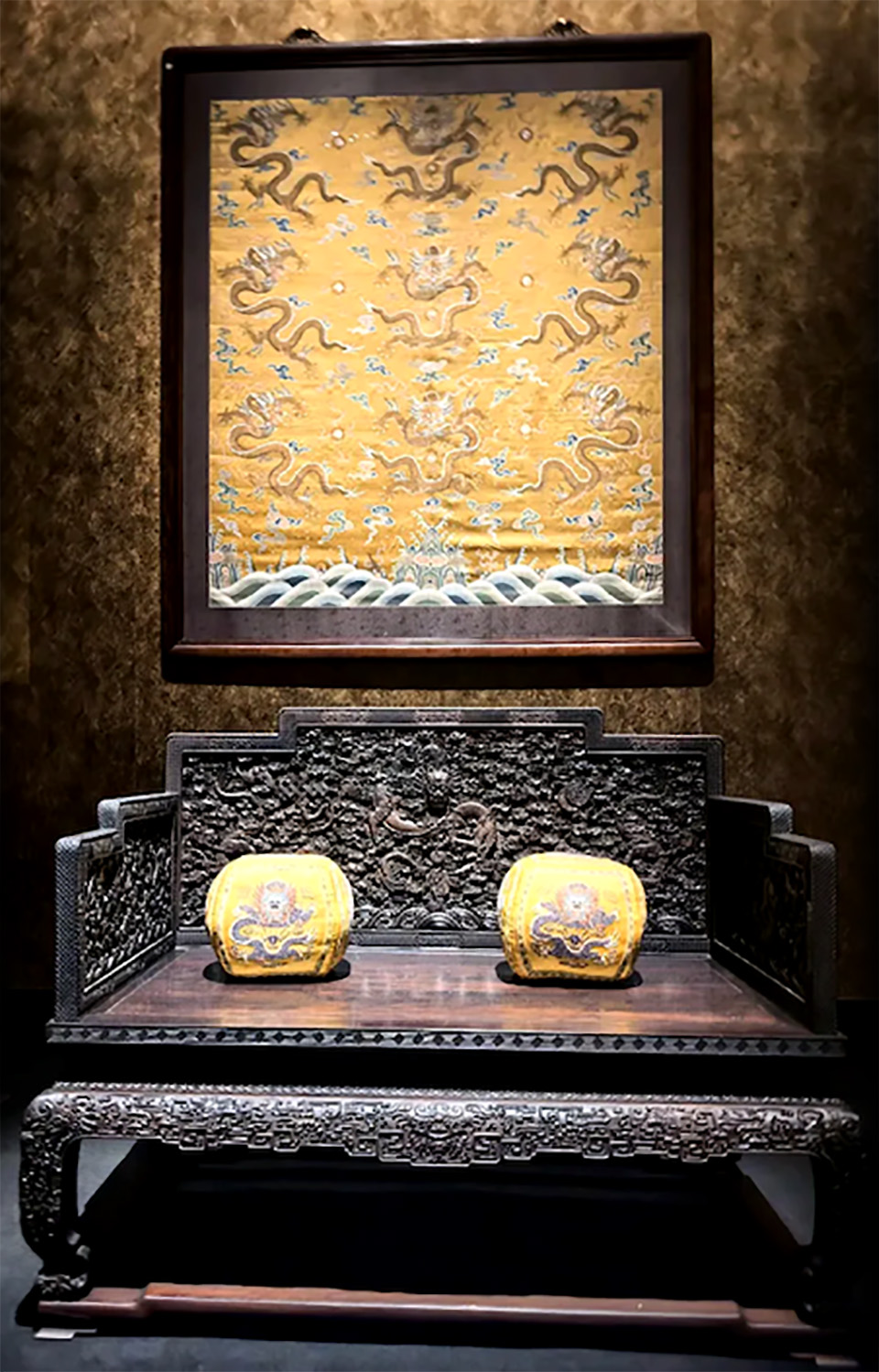

The Inexhaustible Treasury: From Object to Cultural Gene

"The Inexhaustible Treasury" is not just the exhibition’s final section, but a philosophical elevation of its curatorial intent. Originating in Buddhist scripture, the term has been reinterpreted by generations of collectors as a guiding principle of cultural stewardship—not mere accumulation, but transmission, interpretation, and generational sharing of knowledge.

From Su Shi’s use of the term to the Qianlong Emperor’s compilation of the Shiqu Baoji, private collections have long served as vessels of public memory through cataloguing and discourse. Today’s private collectors continue this tradition through scholarship, publishing, exhibitions, and education.

The exhibition embodied this ethos: spanning oracle bones to porcelain, Buddhist icons to imperial artifacts, it reflected a well-organized and collaborative private collecting network. More than wealth or taste, it signaled a collective shift toward cultural responsibility.

Highlight Artifacts:

34 Shang oracle bones with inscriptions: First public appearance, covering sacrificial rituals, warfare, hunting, rainfall, and tribute—"living texts" of Shang civilization.

Western Zhou "Xi Jia Pan" Bronze Basin, 5th Year of King Xuan: 133-character inscription, regarded as the oldest known intact bronze inscription in private hands.

Warring States gold and silver inlaid glass square hu: Technically complex, vibrantly colored; pinnacle of Warring States luxury aesthetics.

Han kneeling jade official lamp and dish: The only known jade figurine lamp; archaeological type specimen.

Northern Song Ru ware celadon basin: Rare surviving example; glaze like frozen fat, sky-blue with icy cracks; pinnacle of Song aesthetic.

Southern Song official kiln octagonal string-patterned vase: Based on Zhouli bronze vessels; refined glaze embodies literati philosophy.

Yuan blue-and-white jar with scrolling lotus: Monumental form, richly glazed, representing early Sino-foreign fusion.

Ming Chenghua doucai "chicken cup": Exhibition’s star item; first shown in Shanghai since 2015; from Liu Yiqian’s collection.

Qianlong gilded bronze musical clock with Eight Immortals of Penglai: Merges Western clockwork with Qing court aesthetics.

Ming Hongxi/Yongle imperial jade seal of Empress Renxiao: Only known surviving ancestral temple seal.

Kangxi famille-verte Twelve Months flower cups: One for each lunar month with matching poems; epitome of Kangxi imperial porcelain.

Qianlong carved cinnabar lacquer throne with cloud-dragon and bat motifs: Nine dragons, cloud-and-lotus design; symbolizes imperial prosperity.

Through this systematically curated exhibition, visitors could appreciate not only the artistic beauty of Chinese antiquity but also understand the cosmological, political, and philosophical worldviews embedded in these objects. More importantly, all this was organized not by the state, but by private collectors. No longer passive custodians, they have become cultural collaborators, using exhibitions as platforms, knowledge as bridges, and social responsibility as motivation.

As Liu Yiqian said: "Antiques are history frozen in time, but they should not be locked away. The life of culture lies in sharing and dialogue." Members of our collectors club echoed this sentiment. Truly responsible collectors are increasingly using exhibitions, publications, research, and education to reintegrate Chinese art into its civilizational context, with private museums playing a growing role in our cultural future.

Collectors Reflect: Beyond Objects, Toward Civilizational Soul

In post-exhibition discussions with members, we heard recurring sentiments:

"True private collecting has moved beyond questions of ownership. It is becoming a key medium for cultural communication and narrative innovation. Each oracle-bone inscription carries ancient cosmology; each crackled Ru-glaze reflects the Song pursuit of harmony."

Senior collectors noted this type of exhibition is no longer just about display; it is a practice of "civilizational restoration." Objects no longer sleep in safes but are revived in public space. Young collectors, especially, are increasingly interested in scholarly frameworks, narrative curation, and digital dissemination. This shift toward "knowledge-driven collecting" suggests a more public-oriented and structurally integrated future for private collections.

Looking ahead, the development of China’s private collectors and museums may focus on three core directions:

Institutional Integration and Regulatory Normalization

Establish legal frameworks and provenance systems to transition private collecting from personal behavior to a structured cultural mechanism. Policies around donations, shared exhibitions, and digital registries should facilitate resource integration.

Knowledge-Driven Curatorial Narratives

Curatorial practice is evolving from static display to interpretive storytelling. Sections like "Longevity of Metal and Stone" and "Vessels Carry the Way" exemplify this shift. Increasing collaboration between collectors and academia will advance the transition from "seeing objects" to "understanding civilization."

Generational Cultural Identity and Aesthetic Education

Break the stereotype that collecting belongs to older generations. Through digital curation, social media, and interactive education, transform private collections into shared cultural assets. Future private museums should be not just exhibition spaces, but incubators of youth cultural identity.

The Role of Private Museums: From Display to Cultural Infrastructure

The "Grand View of Heaven and Earth" exhibition sent a clear message: Chinese private museums are transitioning from mere "showrooms of wealth" to platforms for cultural production and knowledge dissemination.

Led by institutions like the Long Museum, this new generation of private museums exhibits four strategic advantages:

Resource Integration

They systematize rare objects from fragmented private holdings, filling gaps in national research on niche or underrepresented fields. Private capital is becoming a constructive force in cultural rebuilding.

Cultural Communication

Through curatorial professionalism, publications, and digital outreach, they enhance public participation and exhibit greater agility in responding to market and cultural trends.

Academic Support

More exhibitions are supported by dedicated research teams, integrating academic discourse into curatorial logic. Interdisciplinary collaboration enables richer storytelling and positions private museums as nodes in the knowledge network.

Innovation in Cultural Capital Mechanisms

With digital exhibitions, art funds, and cultural derivatives, private collections are evolving from static "symbols of wealth" to shared, extendable cultural capital. This is shaping a uniquely "Chinese path to cultural capital" driven by civil society, fueled by knowledge, and grounded in public engagement.

However, it is equally important to confront the real challenges these institutions face — including outdated legal protections, persistent financial pressures, and questions surrounding the provenance and compliance of collections. To ensure the sustainable development of private cultural institutions, a coordinated effort is urgently needed in the following areas:

- At the policy level: establishing more targeted and supportive regulatory frameworks;

- At the societal level: strengthening public awareness and trust in private cultural platforms;

- At the educational level: fostering a shared understanding that collecting is an essential part of cultural engagement.

Private museums should no longer be seen as trophy halls of wealth but as experimental spaces that carry civilizational narratives, stimulate public thinking, and nurture new cultural models.

Collecting is Not Ownership, but the Rebuilding of Cultural Memory

"Grand View of Heaven and Earth" not only revisited three millennia of Chinese civilization, but also pointed to the future: outside the state system, private collectors and museums are becoming indispensable pillars of the cultural value chain.

This rise should not be dismissed as "showing off" or "private indulgence." It reflects the formation of a new cultural responsibility community. The stewards of tomorrow's civilization will not be cloistered elites, but collectors, curators, museum operators, and public participants who share resources, research, taste, and knowledge.

As collectors, we understand: collecting is not nostalgia, but a mission. The objects we hold in our hands, our museums, and our hearts are not just remnants of the past, but roots of a living civilization and a path to its renewal.

Comments