The True Color of All Things: The Artistic Value and Collecting Strategies of Blanc de Chine

- OGP

- Oct 19, 2025

- 14 min read

By OGP Reporters / Members Contribute File Photos

Oh Good Party

Dehua white porcelain has developed over nearly a thousand years, from its Song-Yuan beginnings, through its Ming-Qing maturity, to its contemporary revival. It is not only the representative of “whiteness as the ultimate” in Chinese ceramic art, but also a unique case within global art history, religious exchange, and materials science. The collecting strategy of Dehua porcelain is not merely the pursuit of high prices, but the establishment of value through three dimensions: provenance, technique, and art historical significance. In today’s art market, Dehua porcelain is in a steady stage of “top-end price authority combined with mid-range liquidity,” making it a category that simultaneously possesses “scholarly collecting value” and “investment operability.”

In the past decade of the international auction market, Dehua blanc de chine has shown stability. At Sotheby’s Spring Auction in 2024, a late-Ming Guanyin figure inscribed with the mark of He Chaozong fetched approximately USD 780,000, setting a new record in recent years for works of this type. At Christie’s London, multiple 17th-century Dehua Guanyin figures consistently achieved hammer prices in the range of GBP 4,000–15,000. Dehua blanc de chine is supported both by the high prices of top masterpieces and the steady market for mid-tier works, giving it both “scholarly collecting value” and “entry-level accessibility.” This market stratification makes Dehua blanc de chine highly attractive in collecting: it satisfies academic research and historical inquiry, while also allowing collectors to build collections at various price levels.

The Historical Value of Dehua Blanc de Chine

According to its historical development, we may divide it into “five periods”: the Germination Period (Song–Yuan), the Flourishing Period (Ming), the Continuation Period (Qing), the Decline and Transformation (Late Qing–Republican Era), and the Revival and Transmission (Post-1949 to the present).

The earliest Dehua white porcelains can be traced back to the Song dynasty, when they were influenced by northern Ding ware and Jingdezhen qingbai ware, beginning attempts at refining kaolin and firing at high temperatures. By the Yuan dynasty, Dehua blanc de chine gradually departed from the shadow of qingbai; the body became denser and finer, the glaze more lustrous, and the whiteness further improved, laying the foundation for the later “ivory white.”

In the mid-to-late Ming dynasty, Dehua blanc de chine reached its peak: with extremely low iron content, refined and white bodies, and glaze as creamy as lard, it developed its distinctive “ivory white” and “pork-fat white.” Sculpture art flourished, with famous craftsmen such as He Chaozong emerging. Representative works included Guanyin figures, Luohans, and refined scholarly objects. Large quantities were exported to Europe, especially via Portuguese and Spanish maritime routes, where they were known as Blanc de Chine and had a profound impact on European taste and the development of white porcelain.

In the Qing dynasty, Dehua blanc de chine continued to develop with increasingly refined craftsmanship, with religious figures still dominating. During the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong reigns, some Dehua blanc de chine was made for the court. Exports also intensified; European religious groups and aristocratic classes widely collected them. Many Dehua porcelain sculptures were converted into Western-style candlesticks or Virgin Mary figures, serving as typical carriers of cross-cultural exchange.

By the late Qing period, due to war, maritime restrictions, and the dominance of the Jingdezhen imperial kilns, Dehua blanc de chine declined in both output and influence. During the Republican era, production continued but focused more on local consumption, with fluctuating artistic standards.

From the 1950s onward, Dehua kilns resumed production under state organization for research and protection. Master artisans emerged, and Dehua blanc de chine was re-recognized domestically as a representative of “Eastern ceramic sculpture.” After the 1970s, Dehua blanc de chine works were presented as national gifts, enhancing their international reputation, marking the era of revival and transmission. Since the 21st century, Dehua has become one of the world’s renowned ceramic production centers, known as the “Porcelain Capital of China.” Contemporary Dehua blanc de chine, while preserving traditional Guanyin, Buddhist figures, and scholarly objects, has integrated modern design, sculptural language, and utilitarian wares, forming a new landscape where tradition and modernity coexist. In 2015, the “Firing Techniques of Dehua Blanc de Chine” was inscribed on China’s National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Today, Dehua blanc de chine is not only a hot topic for collectors but also an important cultural emblem of Chinese ceramics in global exchange.

Typical Craftsmanship

The distinctive “mutton-fat white” texture of Dehua blanc de chine arises from its special processes:

Selection of Materials and Clay Preparation

Based on a low-iron formula using kaolin and porcelain stone, repeatedly washed and refined to ensure purity and plasticity.

Forming Methods

Wheel-throwing, press-molding (with sectional molds joined together)

coil-building, and hand sculpting are all used. For Dehua figures and Buddhist sculptures, the integrated process of “subtractive modeling, trimming, line-carving, and appliqué” is especially emphasized.

Drying and Bisque/Single Firing

Depending on structural needs, pieces may undergo bisque firing or direct high-temperature single firing, carefully controlling stress and shrinkage.

Glazing and High-Temperature Firing

Usually coated with transparent or opacified transparent glazes, fired in oxidation atmospheres at about 1280–1350°C, resulting in the warm, translucent “mutton-fat white” finish.

Kiln Loading and Saggars

Historically, saggars and kiln supports were widely used to prevent glaze adhesion and to maintain whiteness and surface cleanliness.

Though this reflects common practice, different Dehua workshops varied in recipes, firing curves, and kiln-loading techniques, contributing to subtle stylistic distinctions across periods and makers.

Historical Value and Art Historical Positioning

• Sculptural Tradition and the “He Chaozong System”

He Chaozong (c. 1505–1580) was the most renowned sculptural master of Dehua. His Guanyin figures are famous for their high cranial long faces, downcast eyes in meditative concentration, and sharply defined yet rhythmically flowing drapery. The common seated Guanyin, with its robe simple yet imposing, radiates a serene and solemn religious atmosphere. He Chaozong’s sculptures are acclaimed as “the pinnacle of Dehua white porcelain figures.” His methods absorbed the realism and dignity of Song and Yuan sculpture, while integrating the refined elegance of Ming literati aesthetics. Qing dynasty craftsmen often took the “He school” as a paradigm, even directly inscribing “He Chaozong” marks, using it as both an artisanal and devotional stamp of authority. From this, academia and the collecting world have established the “He Chaozong system” as an evaluative benchmark: Dehua Guanyin figures that feature dignified posture, flowing drapery, and tranquil expressions are commonly referenced against his style.

• Global Dissemination and Export History

From the 17th century onward, Dehua white porcelain entered Europe in large quantities via the Maritime Silk Road and was called “Blanc de Chine” (French for “Chinese White Porcelain”). These works were not only used in religious contexts—Guanyin figures were often transformed into images of the Virgin Mary or Madonna and Child—but also became prized collectibles in European courts and aristocratic circles.

Notable collections include: the Louvre Museum in Paris, which houses several 17th-century Dehua Guanyin figures that testify to cross-cultural translation in religion and art; the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, which preserves a large number of Dehua Guanyin, Arhat figures, and censers, making it a major center for the study of Ming–Qing export porcelain; the “Japanese Palace” in Dresden, where Dehua porcelains influenced the Electorate of Saxony in founding Europe’s first hard-paste porcelain kiln (Meissen). In 17th–18th century Europe, Dehua white porcelain became highly fashionable, exerting profound influence on Baroque and Rococo sculpture and interior decoration; many European porcelain manufactories (such as Meissen and Chantilly) directly imitated Dehua Guanyin and Madonna figures.

• Material and Technical Value

Dehua porcelain clay is low in iron and titanium, producing a semi-translucent milky white after firing, with fineness comparable to jade, praised in the West as “mutton-fat jade among porcelains.” The key craftsmanship lies in the combined processes of “subtractive modeling—trimming—incising—appliqué,” which together achieve the flowing movement of drapery and the softness of facial features. This integrative sculptural method differs from the painted blue-and-white tradition of Jingdezhen, aligning it more closely with pure sculpture.

Modern scientific research: X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis reveals that Dehua porcelain bodies contain extremely low Fe₂O₃ content (generally <0.5%), which is critical to its whiteness and warmth. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) shows that at high temperatures Dehua porcelain forms a dense microcrystalline structure with tightly bonded particles, explaining its “semi-translucent—lustrous” optical qualities. Thermal analysis and firing-curve studies confirm that Dehua artisans mastered kiln temperature control between 1280–1350°C, allowing body densification without deformation. These physical and chemical data are forming the “material fingerprint” of Dehua porcelain, aiding in distinguishing genuine works from forgeries and building a scientific authentication system.

The historical value of Dehua white porcelain lies not only in its distinctive artistic style (the He Chaozong system), but also in its global dissemination and impact on world ceramic industries, as well as in the unique “ceramic identity” defined by modern materials science. It is simultaneously a masterpiece of Ming–Qing religious sculpture and a node of exchange and integration in global art history.

Market Temperature and Price Bands (Based on Recent Auction Records)

• Museum Level / Late Ming–Early Qing Early Sculptures (Apex Level)

Top-tier large standing Guanyin figures inscribed with “He Chaozong” are considered apex assets at leading international auction houses. In March 2025, Sotheby’s auctioned a Dehua standing Guanyin, c. 52 cm in height, titled “By He Chaozong, 17th century,” with a pre-sale estimate of USD 600,000–800,000. The final publicly recorded hammer price was USD 635,000 (Sotheby’s, 2025). This demonstrates that the contemporary market continues to show strong buyer demand and valuation benchmarks for large-scale sculptures confirmed as He-school works in good condition.

• High-End Historical Pieces — Christie’s / Sotheby’s Historical Performance

Christie’s and Sotheby’s have, over the past two decades, repeatedly offered Dehua figures bearing the inscription “He Chaozong” or attributed to the 16th–17th century. Individual results have ranged from several hundred thousand to several million Hong Kong dollars/USD (for example, records from Christie’s 2005, 2014, and 2016 sales all indicate that this category consistently commands the high valuation tier). These records are frequently cited in academic and collecting circles as benchmarks for pricing and authentication.

• Core Segment (17th–18th Century, Medium-Sized Guanyin Figures such as “Guanyin with Child”)

At major auction houses, mid-sized 17th–18th century Dehua Guanyin with Child figures typically carry catalog estimates and results in the range of approximately €4,000–€6,000. Actual results depend on size, completeness, inscriptions, and provenance (for example, Sotheby’s April 2025 catalog listed a 17th–18th century Guanyin with Child with an estimate of €4,000–€6,000). This reflects a stable “core segment” market in international sales, though results vary significantly with condition and provenance documentation.

• Ordinary Antiques and Modern/Contemporary Works (Mass Market)

In smaller Western auction houses, online sales, and regional markets, Dehua Guanyin and related blanc de chine items show wide price variation: from a few hundred to several thousand USD. For example, multiple sales at local and online auctions have been recorded in the €100–$4,000 range. These pieces are often later in date, repaired, or lacking reliable evidence of authenticity/inscription. Their market performance is more volatile, with easier liquidity but difficulty in achieving consistent premium appreciation.

Auction Houses and Valuation Reference Points (Practical Reminders for Investors)

• Provenance

Works with long-standing museum or notable collection provenance (e.g., early Western collectors, published catalog references) significantly enhance valuation and saleability. Sotheby’s large He-marked Guanyin carried a provenance note: “American Private Collection, acquired between 1971 and 1981,” underscoring the importance of such provenance for final hammer results.

• Inscriptions and Restoration

He Chaozong inscriptions, seals, clay quality, and glaze characteristics are the core focus of authentication. Minor restorations, base replacements, or glaze contamination can substantially affect mid-to-high-tier valuations (auction catalogs and condition reports typically detail such issues).

• Market Seasonality and Bidding Environment

Auction estimates serve as guidelines; actual results are heavily influenced by in-room bidding atmosphere, buyer rosters (private collectors vs. institutions), and seasonal themes (e.g., dedicated Dehua sessions).

Specific Auction Examples

Sotheby’s: “A magnificent and exceptionally large ‘Dehua’ figure of standing Guanyin, By He Chaozong, 17th century” — estimate USD 600,000–800,000; sold for USD 635,000 (Auction date: March 2025).

Christie’s: A Dehua Guanyin with “He Chaozong” mark — recorded hammer price GBP 131,200 in 2005; further notable high-estimate/sales in 2014 and 2016, confirming its placement in the high-end category.

Sotheby’s catalog (April 2025): A 17th–18th century Guanyin with Child estimated at €4,000–€6,000, serving as a reference for the typical core segment.

Bonhams and other medium-size auction houses: numerous listings and sales of “He-marked” or ordinary Dehua figures, demonstrating that the market accommodates both the high-end and a large volume of lower-entry-level circulating works (Bonhams and regional catalog/transaction records referenced).

Authentication and Risk Warnings

Late Ming–Early Qing Sculptures (He Chaozong System)

Identification points: sharply cut drapery folds, serene facial expressions, dignified and composed posture; commonly bear impressed intaglio/relief seals reading “He Chaozong,” though later-added seals must be approached with caution.

Risks: counterfeit inscriptions, pieced-together restorations, and over-glazing. Priority should be given to examples with clear provenance and inclusion in authoritative catalogues.

Ming–Qing Literati “Qinggong” Works and Export Wares

Identification points: small ritual vessels, animal figures and Boshan censers, ewers, covered jars, etc.; frequently seen in old European collections.

Focus: old collection labels, export records, and archives of European antique dealers.

Late Qing–Republic of China (Early 20th Century) Works

Advantages: relatively accessible in price, suitable for building theme-based collections (Guanyin, Arhats, child figures, auspicious beasts).

Risks: uneven quality of craftsmanship; evaluation depends on tactile feel and glaze surface. Price reference range is wide.

Contemporary Dehua Masters and Young Creators

Advantages: high originality and communicability, with the possibility to directly establish documentation with artists/institutions.

Focus: endorsements such as exhibitions, awards, and institutional collections, as well as the reproducibility of works (editions, molds). Young artist groups exhibited provide an important observation window into “future potential.”

Provenance of Collections

If the goal is capital preservation and appreciation, priority should be given to large late Ming–early Qing sculptures with clear provenance (museum/private provenance) that can be attributed to the He school or substantiated through archaeology/documentation. Catalogue records, old collection history, and authoritative transaction records act as the ballast of value. Such few masterpieces achieve the highest premiums at major auction houses. If the goal is entry-level collecting or public display, one may consider medium/small 17th–18th century typical figures or fine modern works (budget ranging from several thousand to tens of thousands), but condition and corroborative provenance evidence must be scrutinized carefully. In general, inscriptions and seals also require attention: He Chaozong seals must be evaluated with stylistic and technical analysis; one must avoid the fallacy of “seeing a seal and assuming authenticity.”

Material and Technical Indicators

Dehua porcelain body and glaze are low in iron, with a warm, lustrous glaze; old examples often display kiln scars, natural oxidation encrustations, and signs of use. Beware of “artificial aging” and composite restorations. Hairline cracks, firing seams, missing fingers, and secondary glazing all significantly affect valuation; condition is extremely sensitive to value. Scientific testing is very important: XRF/microstructural analysis can corroborate body and glaze characteristics; thermoluminescence has limited applicability for high-fired porcelain and should not be overly relied upon as a single test. The market for forgeries is mature, ranging from “new works made old” to “old pieces heavily reworked,” making counterfeits and later additions among the greatest risks.

Information Asymmetry and Liquidity Divergence

Distinctions between studio editions and handmade unique works, as well as lack of transparency regarding editions and molds, remain an issue. Top-tier items enjoy strong liquidity and clear price discovery, while mid-to-lower-end results fluctuate considerably.

Recommendations for Collectors – Practical Guidelines

“Look before you buy” — Establishing a visual and tactile “textural memory”

It is recommended that newcomers first engage in extensive observation of museum exhibitions and authoritative published catalogues, such as the collections of the National Museum of China, the Shanghai Museum, the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), in order to cultivate a direct sense of the porcelain body, glaze, and the expression of figures in Dehua white porcelain.

During auction previews (Sotheby’s, Christie’s, China Guardian, Bonhams, etc.), it is essential to inspect similar lots in person, carefully observing the body and glaze details from different periods as well as traces of restoration. Over time, one can form a “textural memory” of the glaze quality of “mutton-fat white” and the sculptural rhythm, thereby improving the ability of discernment.

“Provenance is king” — Prioritize works with reliable origins

In the high-end market, the core value does not lie in size or subject matter, but in provenance and documentation: works recorded in exhibitions or publications, having participated in renowned museum/academic exhibitions, or included in authoritative catalogues (such as the Blanc de Chine series). Established collectors tend to prefer works with old provenance, for example, from early 20th-century Western collectors (such as French missionaries or objects circulated through the Dutch East India Company), or with past sales records in well-known auction houses. These can serve as endorsements for a piece. When reviewing auction catalogues, buyers should carefully read the appendices (provenance), condition reports, and may request restoration records or laboratory test reports from the auction house.

“Building in gradients” — Systematically constructing a collection

It is not advisable to rush immediately toward million-dollar “He Chaozong” benchmark figures. Instead, one may begin with mid-market, high-quality small-scale Guanyin statues, child figures, censers, or ritual vessels, thereby establishing thematic coherence while gradually becoming familiar with market trends. Once comparative knowledge has accumulated to a certain degree, one can then expand into iconic subjects (such as “He Chaozong Guanyin” or groups of Luohan figures), progressively constructing a pyramid-shaped collection structure: foundational pieces → core pieces → benchmark pieces.

“Parallel verification” — Multiple methods for cross-checking

A common practice is the “threefold parallel verification,” which avoids decisions based solely on “visual judgment” or “market reputation,” thereby reducing the risk of forgeries or composite works. First, from the perspective of stylistics, compare facial expressions, drapery folds, posture, and historically established paradigms (particularly within the “He Chaozong system”). Second, examine technical indicators: the purity of the clay, the thickness of the porcelain body, traces of firing supports, and the layering of the glaze. Third, and most importantly, use scientific testing, such as XRF compositional analysis or SEM microstructural observation, to confirm the low-iron kaolin formula and firing characteristics. Data obtained through testing are more reliable than the naked eye.

“Long-termism” — Enabling continuous value appreciation through scholarship and culture

The true value lies not only in the purchase price, but in whether a piece can be provided with scholarly context and cultural substance. Collecting itself has long been both the cultivated interest of literati and a method of preserving value, so many collectors publish books and catalogues alongside their acquisitions. For example, submitting works for academic study, or contributing to relevant journals and publications. Beyond papers and publications, lending to exhibitions is also very common: collectors loan their pieces to museums or professional institutions, thereby enhancing the scholarly visibility of their works. In addition, digital dissemination is increasingly important: producing high-resolution images and research reports, uploading them to online databases or exhibitions. Through such ongoing empowerment, the value of the work goes beyond the marketplace, gaining both scholarly and cultural endorsement, which in turn enhances its future premium potential.

Thus, the core of Dehua porcelain collecting lies in eye training + provenance verification + systematic structuring + scientific authentication + scholarly empowerment. Only by forming a long-term plan and following a “scholarship + market” dual pathway can one avoid short-term speculative traps and achieve a true balance between collecting and investing.

Other Exhibitions and Academic Resources

The exhibition “China White: Dehua Porcelain” was held in Shanghai from July 18 to September 19, 2025. The exhibition was themed around Dehua porcelain and structured into three sections: “Prosperous Times, New Creations / Historical Excavation / The Future of Craft.”

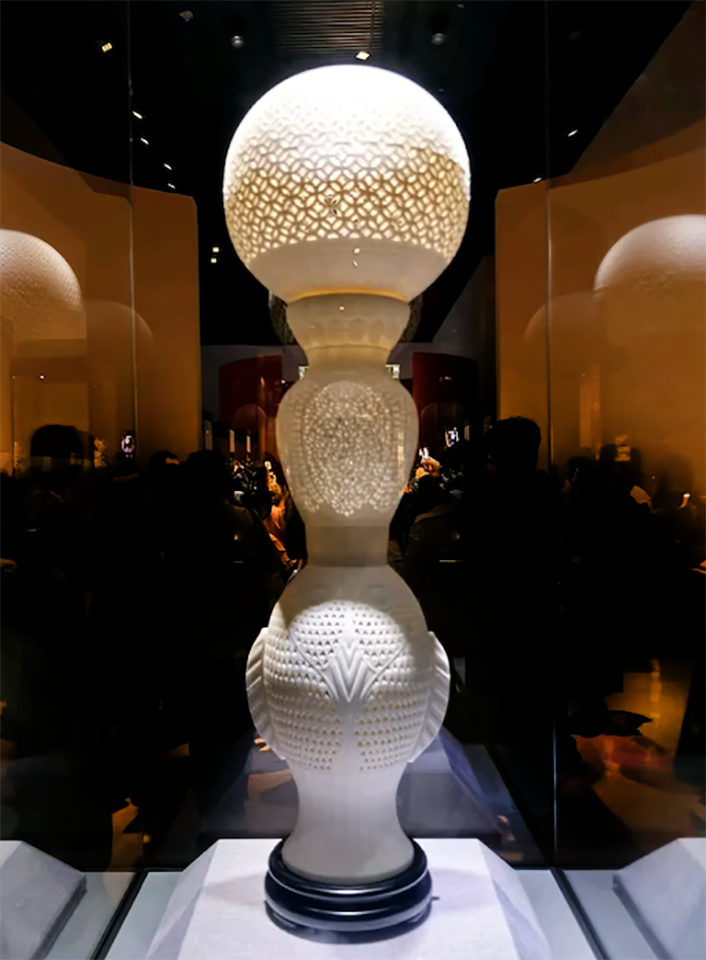

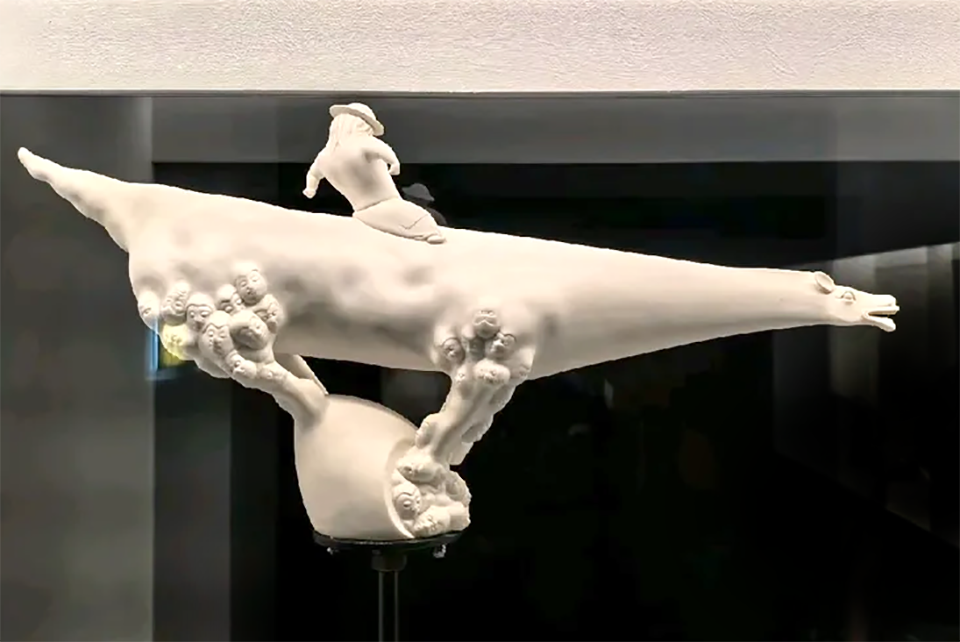

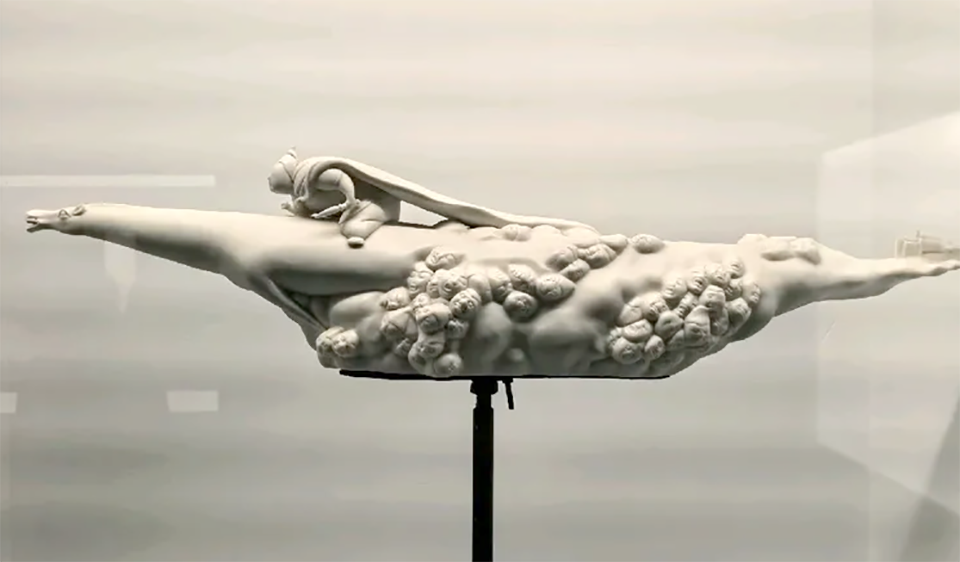

The first section focused on contemporary Dehua masters “upholding tradition while innovating,” showcasing representative works such as Expo Tripod, Mythology, and Brilliant Colors · Wish-fulfilling Buddha of Many Treasures.

The second section was organized around the archaeological installation of the Taixing Shipwreck and displayed Dehua porcelain across dynasties in a timeline format, tracing the lineage of objects from the Xia and Shang periods through the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing.

The third section systematically presented the contemporaneity, conceptuality, and experimental explorations of young ceramic artists, outlining the future landscape of Dehua porcelain.

The above information can be found in mainstream media and institutional reports, serving as useful material for review and reference. Meanwhile, the three-part structure of “History — Contemporary — Future” provides a multidimensional presentation of Dehua porcelain within the contexts of craft history, export history, and contemporary ceramic art, making it an ideal “first lesson” for collectors entering the field.

Exhibition highlights included: Expo Tripod, Mythology, Brilliant Colors · Wish-fulfilling Buddha of Many Treasures, Pearl of the Orient, Heavenly Maiden Scattering Flowers, Subduing the Tiger, Tang Charm, Purple Aura from the East, Bonded Vase, Blossoming Wealth Series, and Chinese Character Art · Hundred Family Surnames. These new works collectively embodied the sculptural power and decorative aesthetics of contemporary Dehua porcelain. The Taixing Shipwreck installation, meanwhile, connected export Dehua porcelain with the Maritime Silk Road, reinforcing the narrative of “historical excavation.”

In summary, Dehua white porcelain has developed over nearly a thousand years, from its Song-Yuan beginnings, through its Ming-Qing maturity, to its contemporary revival. It is not only the representative of “whiteness as the ultimate” in Chinese ceramic art, but also a unique case within global art history, religious exchange, and materials science. The collecting strategy of Dehua porcelain is not merely the pursuit of high prices, but the establishment of value through three dimensions: provenance, technique, and art historical significance. In today’s art market, Dehua porcelain is in a steady stage of “top-end price authority combined with mid-range liquidity,” making it a category that simultaneously possesses “scholarly collecting value” and “investment operability.”

Comments