The Collecting Logic of Ancient Sculptural Art — When the Roman Gods and Imperial Memory Endure

- OGP

- 3 days ago

- 11 min read

By OGP Reporters / Members Contribute File Photos

Oh Good Party

When we stand before ancient Roman sculpture today, we are not merely “appreciating antiques,” but confronting a way of thinking that once shaped the world. Rome no longer exists, yet through sculpture it projected its order, ambition, and rationality into time. Sculpture gives history weight and allows memory to exist beyond written records. For this reason, ancient Roman sculpture belongs not only to museums, but to the history of civilization itself. They are not static objects, but witnesses that continue to speak. Collecting ancient sculpture is both a cultural pursuit and a dialogue with history. It demands patience, expertise, and respect. Truly exceptional works—whether Roman Imperial busts or sculptures embodying mythological power—not only preserve value in the market, but also offer collectors a unique resonance in aesthetic experience and civilizational memory.

Echoes of History: When the Roman Gods and Imperial Memory Arrive in Shanghai

At the Shanghai World Expo Museum, Roma Roma: From Olympus to the Capitoline feels like a long-awaited civilizational encounter, allowing ancient Roman art to be re-seen, re-discussed, and re-understood within the rhythm of a contemporary city.

This exhibition is jointly presented by the Shanghai World Expo Museum and National Museums Liverpool. All 131 objects (sets) on display come from the latter’s core collection. National Museums Liverpool is renowned for its extensive collection of classical sculpture, second in scale only to the British Museum, and the works presented here are almost entirely among its most representative holdings. Sculpture, ceramics, glassware, gemstones, and sarcophagus reliefs are placed within a single narrative space, transforming Rome from an abstract historical concept into a tangible and imaginable world.

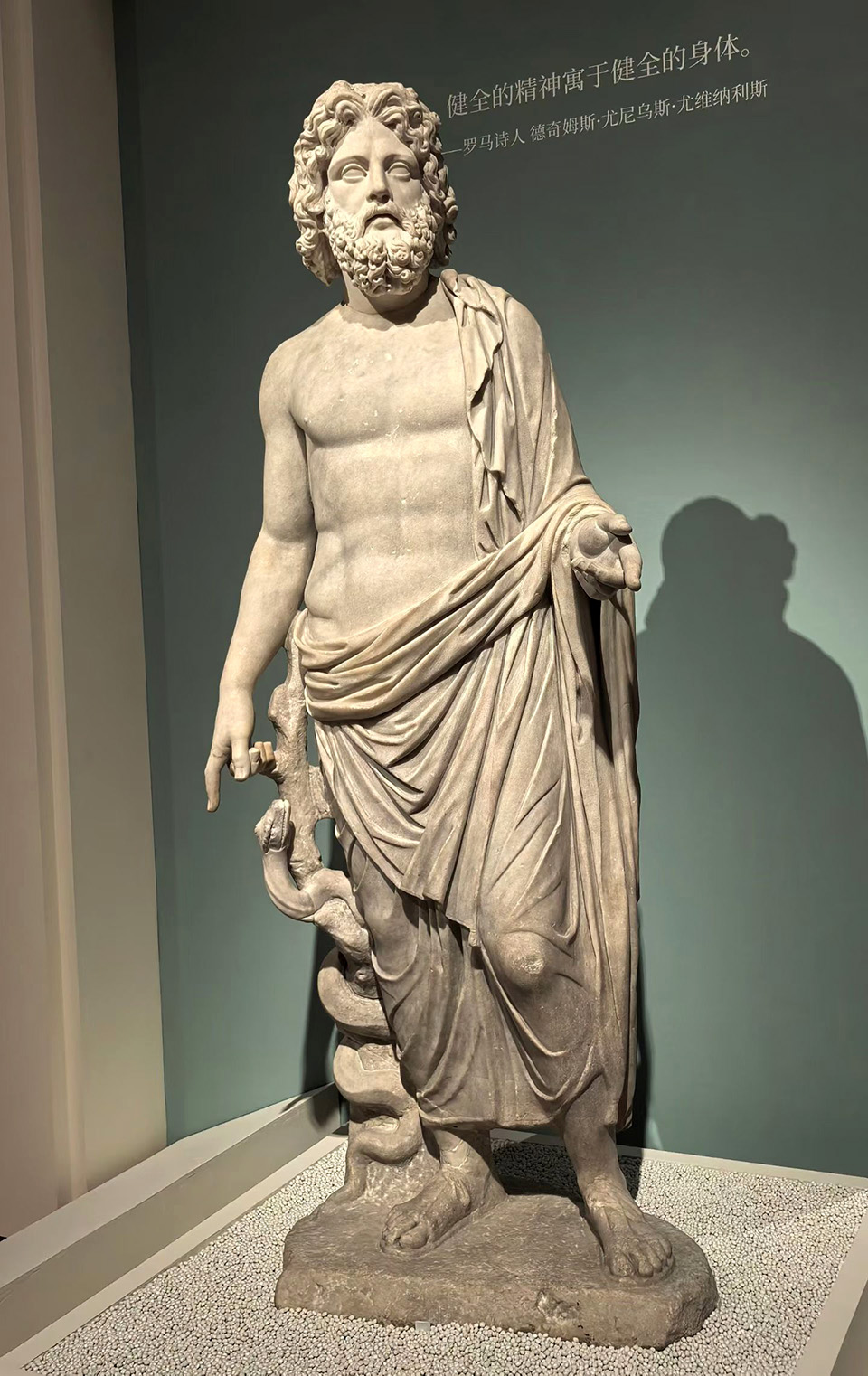

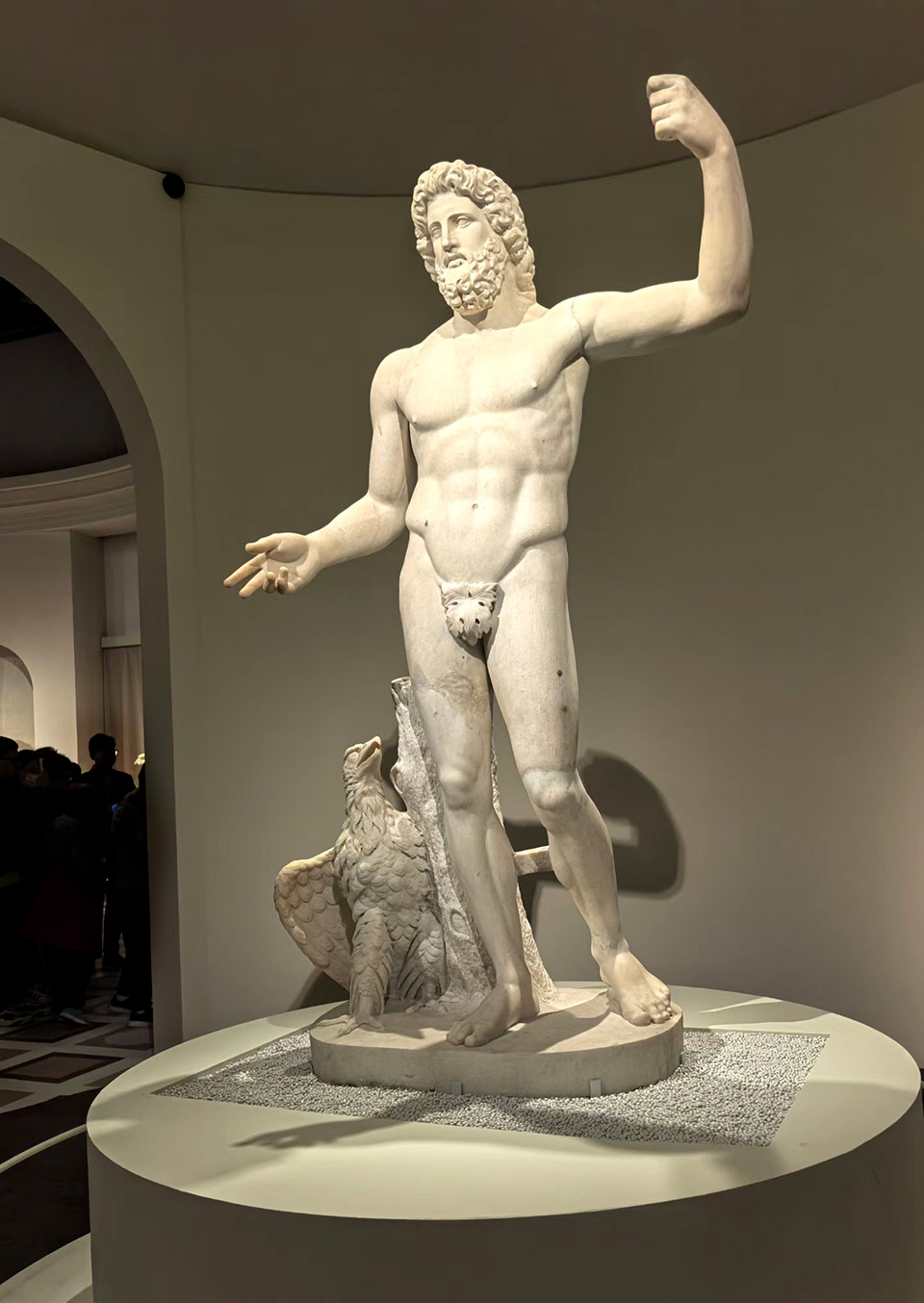

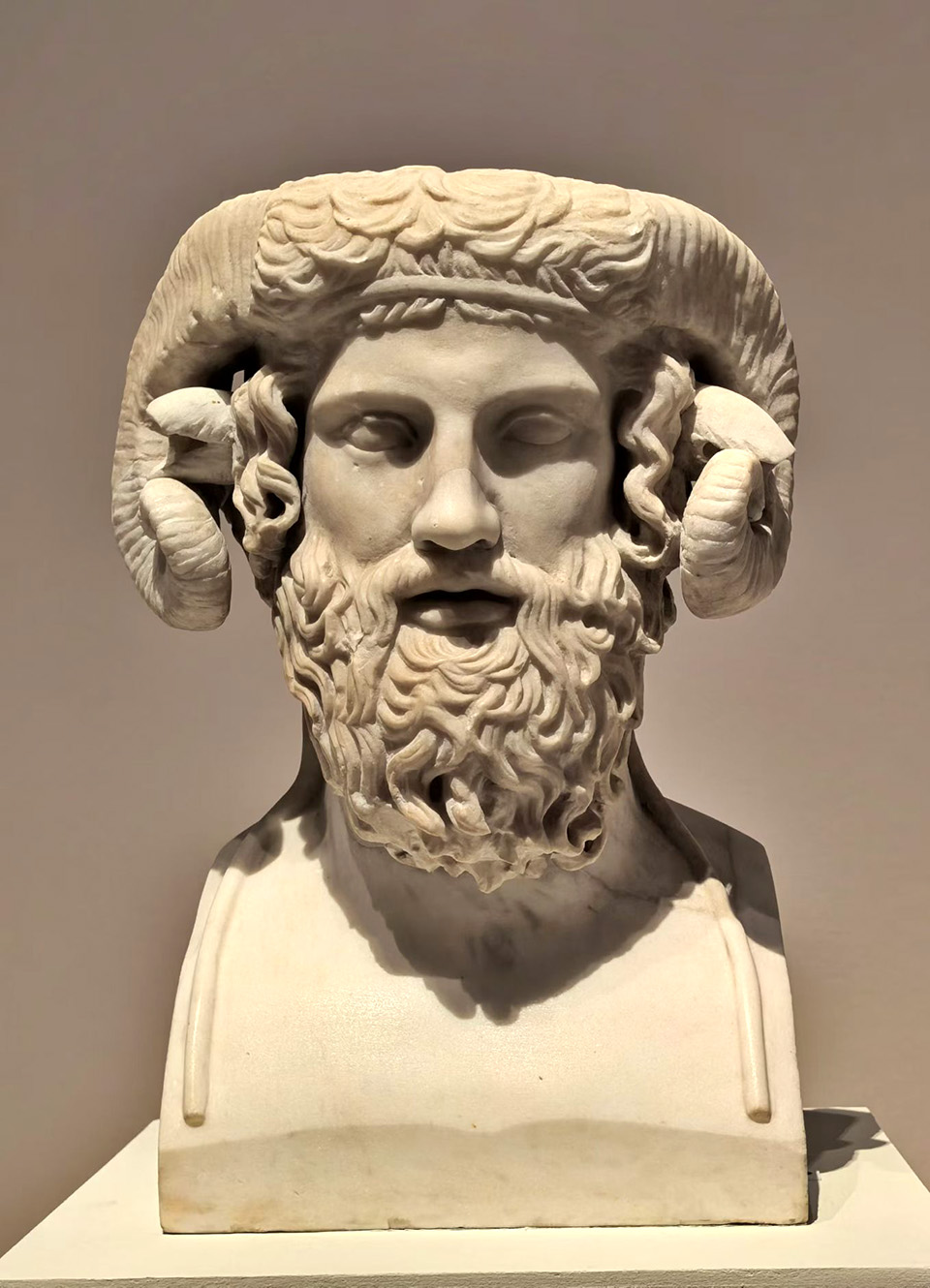

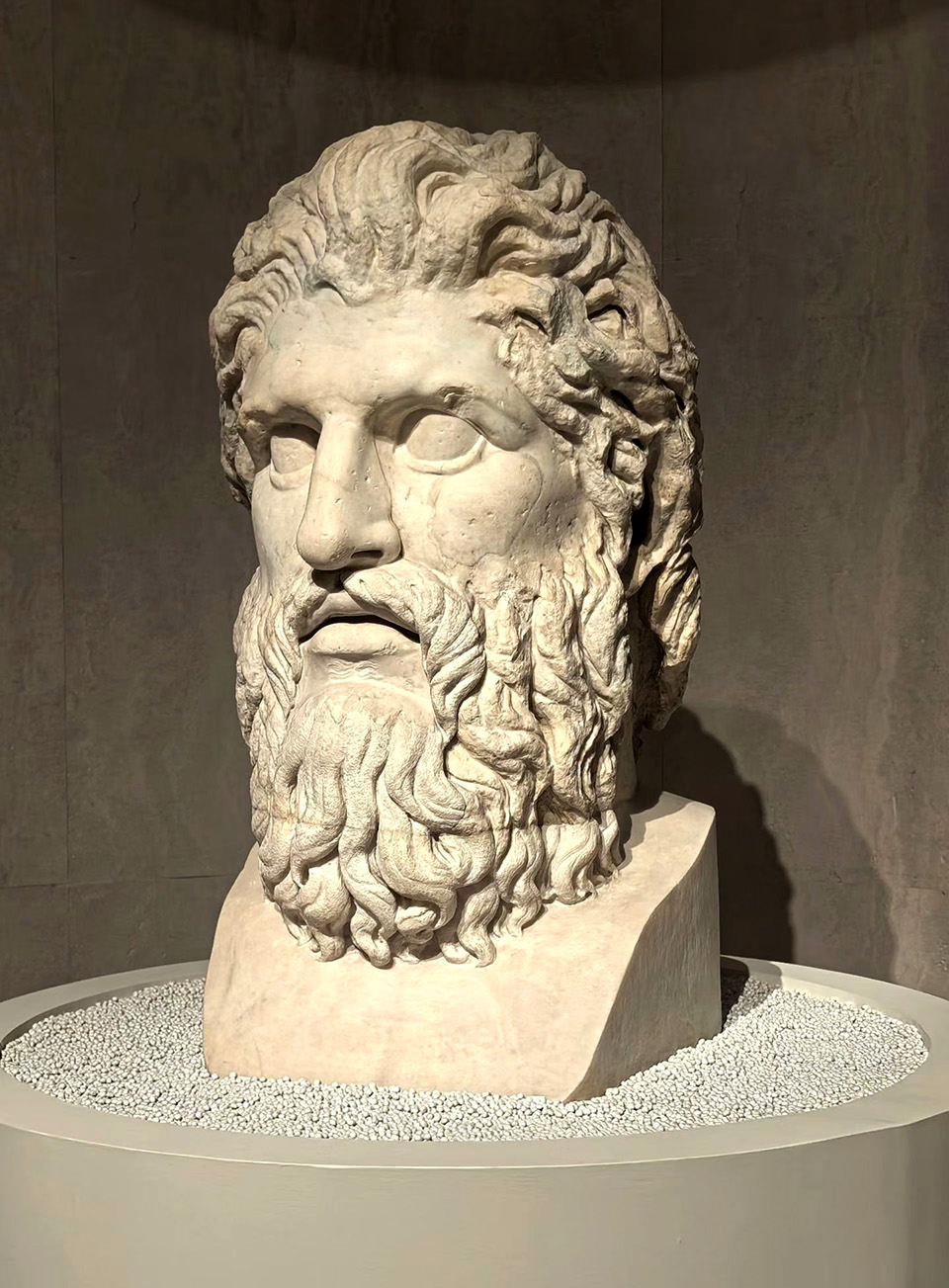

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are first greeted by “The Legends of the Gods.” Here, the spiritual structure of Greek mythology clearly overlaps with the practical needs of Roman political culture. The 2.27-meter-tall statue of Zeus—known as Jupiter in the Roman system—is not merely an image of a celestial deity. He inherits the supreme authority of the king of the gods from the Greek world, while in the Roman context he is endowed with a stronger sense of order and law. Jupiter is not only the wielder of thunder but also the guardian of state oaths and the legitimacy of power. Echoing this is the bust of Poseidon (Neptune), god of the sea and earthquakes. His significance grew during Rome’s expansion—when Rome evolved from a city-state into an empire, the sea was no longer merely a natural space but a conduit for trade, warfare, and colonization. The image of Neptune thus symbolizes Rome’s incorporation of natural forces into imperial order. Minerva (the Greek Athena) represents yet another path of transformation. Originally the goddess of wisdom, warfare, and craftsmanship, she gradually became, within the Roman system, a symbol of rationality, technology, and the capacity for state governance. Her statue in the gallery does not emphasize feminine softness, but instead conveys calmness, restraint, and solidity—precisely the Roman understanding of “wisdom.”

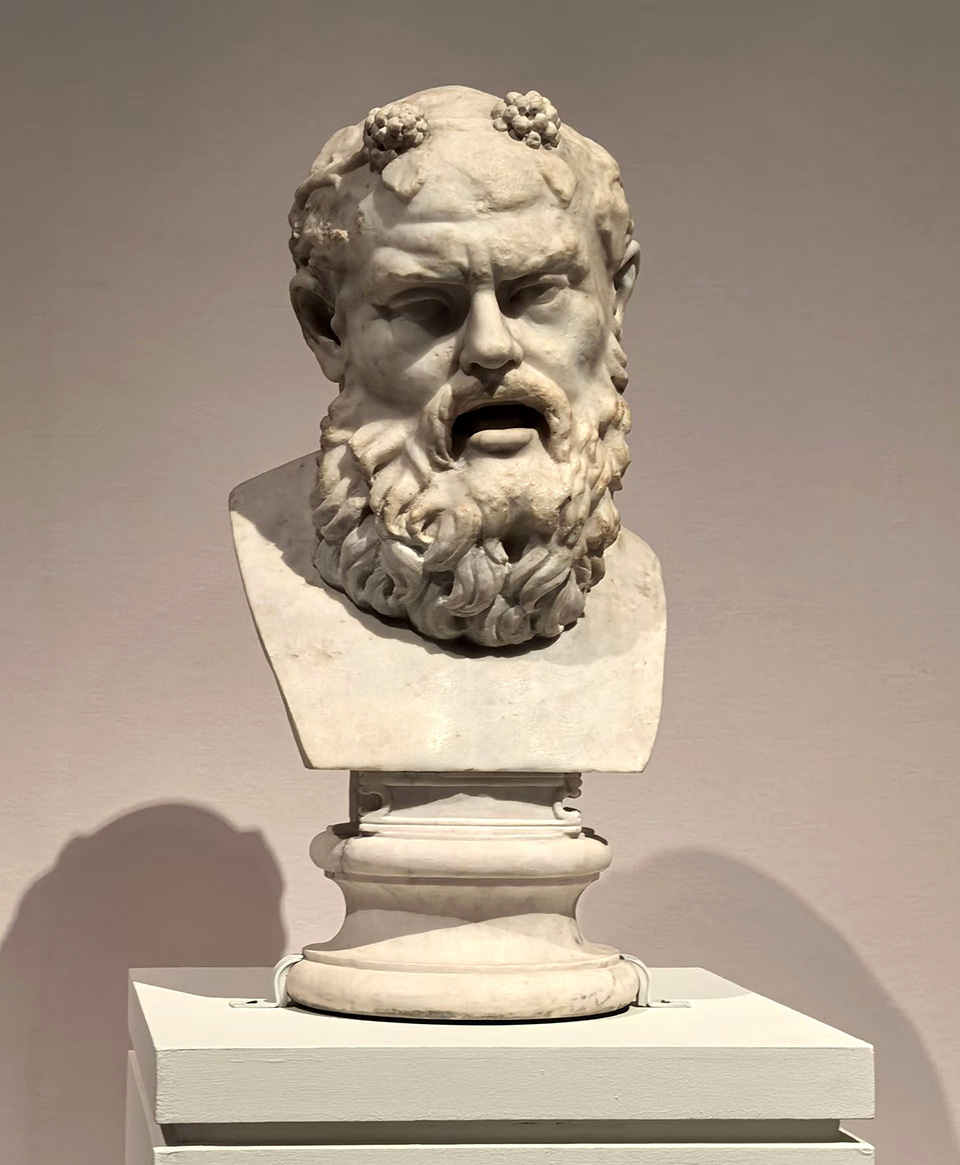

If the gods demonstrate how Rome “inherited” the Greek spirit, the section titled “The Glory of the Empire” reveals how Rome transformed mythology into real political power. Twenty-six portraits of emperors and aristocrats, represented by the bust of Emperor Augustus, form a silent political history. These sculptures do not pursue the idealization of eternal youth; instead, they emphasize facial features, signs of age, and expressive tension—this is the core of Roman portraiture: truth itself is authority.

As the founder of the Roman Empire, Augustus’s image retains rational restraint while subtly suggesting divinity. He did not proclaim himself a god; rather, he allowed “divine order” to be realized through himself. This subtle political aesthetic permeated the entire visual system of the Roman Empire and explains why imperial portraits became the most important visual symbols in public space.

In the section “The Banquet of Life,” another side of Rome gradually unfolds. Ceramics, glassware, gemstones, and mosaics remind us that this empire was not only adept at conquest but also deeply invested in the ritualization of daily life. From banquets to bathing, from domestic furnishings to personal adornment, Romans infused aesthetics, technology, and order into every detail of life. Civilization does not exist solely in grand narratives; it is equally embodied in a wine cup, a mosaic, or a gemstone engraved with the image of a deity.

The curatorial structure of the exhibition follows the dual imagery of Mount Olympus and the Capitoline Hill, pointing to an essential fact: Rome was never a civilization that emerged from nothing. Through absorbing, rewriting, and reorganizing Greek culture, it developed a highly institutionalized, replicable, and expandable civilizational model. It was this model that allowed Rome’s influence to extend far beyond the Mediterranean, profoundly shaping later legal systems, urban structures, political concepts, and artistic traditions. In this sense, every object in the gallery is a “witness” to history. They bear witness to how mythology was used to explain the world, how power acquired legitimacy through art, how an empire rose, and how civilization itself has been inherited, misread, and reinterpreted over time.

When we encounter these Roman gods, emperors, and everyday objects, what truly takes place is not merely a “visit.” It is, rather, an engagement with the artistic value and historical meaning of these silent stones and artifacts—an opportunity to re-examine what order is, what power is, and what enduring echoes civilization leaves behind.

When Deities Took on Human Faces: Ancient Roman History, Mythology, and Sculpture as Witnesses of Civilization

If there is one art form through which ancient Rome can be understood, sculpture is almost impossible to bypass as an entry point. Rome was not merely an empire that conquered the world through force; it was a civilization that shaped order through “images.” Gods, emperors, heroes, ancestors—every significant presence was endowed with a form that could be seen, touched, and remembered. It is within these marbles and bronzes that Rome left behind its way of understanding the world.

The Roman mythological system did not emerge out of nothing; it was the result of a centuries-long process of “cultural absorption.” Before Rome became an empire, it was already deeply influenced by Greek civilization. Zeus became Jupiter, Athena became Minerva, Aphrodite transformed into Venus, and Poseidon was called Neptune. The names changed, but more importantly, their functions were redefined. In the Greek world, Zeus symbolized cosmic order; in Rome, Jupiter was more like a guardian deity of the state, representing law, oaths, and political legitimacy. For this reason, statues of Jupiter often appear in solemn, enthroned poses, gazing over all beings—not a poetic god, but a god of institutions. The same applies to Minerva. She was no longer merely a goddess of wisdom, but a symbol of military rationality and urban order. Her helmet, shield, and calm expression frequently appeared in public buildings and military-administrative spaces. Sculpture here was not decoration; it was part of the language of power.

The greatest difference between Romans and Greeks lay in how they used art.

Greek sculpture emphasized ideal beauty, while Roman sculpture emphasized recognizability, realism, and authority. Roman statues of deities were often more “realistic” because they did not exist solely within belief systems, but also within law, ritual, and public life. A statue of Jupiter in a temple was both a religious object and a symbol of the state; Neptune appeared in harbors, fountains, and public baths, symbolizing control over water and trade; Venus was not only the goddess of love and beauty, but also embodied Roman ideas of lineage and destiny—according to legend, Rome’s ancestor Aeneas was the son of Venus. Thus, every divine sculpture was a piece of myth that had been “institutionalized.”

If mythological sculpture embodied Rome’s “ideal order,” then imperial portraits recorded its “real power.” Ancient Rome was one of the earliest civilizations in human history to systematically use portrait sculpture for political communication. Beginning with Augustus, the image of the emperor was widely replicated, disseminated, and placed in city squares, temples, and administrative spaces throughout the empire. Busts of Augustus often present a youthful, restrained, almost divine face. He was not meant to be seen as an aging man, but as the embodiment of an eternal order. Later emperors, such as Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, gradually allowed age, personality, and the pressures of reality to appear on their faces. These sculptures were not the result of “artistic freedom,” but highly politicized visual documents.

Today, historians study these busts to analyze shifts in power, changes in ideology, and even the psychological state of the empire. Sculpture here becomes testimony more honest than words.

The Birth of Realism: How Rome Changed Western Art

The most profound influence of Roman sculpture on the world lies not only in its subjects, but in its attitude. Romans believed that truth itself had value. As a result, wrinkles were preserved, old age was confronted directly, and failure and exhaustion could also be recorded. This “realism” fundamentally transformed the history of Western art.

It is because of Rome that we now accept that:

• Power can have a face

• History can be “seen”

• The individual can become part of public memory

During the Renaissance, it was through the rediscovery of Roman sculpture that artists once again came to understand the nature of “human beings” themselves. Michelangelo, Raphael, and Bernini all learned from Roman sculpture how to endow the body with spirit.

History can be written, and it can be revised; sculpture, however, often survives silently in ruins as a witness to history.

A statue of a god with a broken arm, a worn imperial bust, is often closer to truth than a complete written history. They record aesthetics, power, and technology, as well as processes of forgetting and erasure. In Roman civilization, sculpture was not merely an art object, but—material evidence of myth, a language of power, and a vessel of memory. They bear witness to how Rome grew from a city-state into an empire, and how, after its collapse, it continued to shape the world.

The Logic of Collecting Ancient Sculptural Art: From Market Records to an Introductory Overview

In the global art market, sculpture has always been one of the most compelling artistic categories. Classical and ancient sculptures in particular not only carry the weight of civilizational history but also remain focal points for major auction houses. Although ancient sculpture appears less frequently at auction than modern and contemporary works, when a top-tier example emerges, it can command astonishing prices.

Recorded high-price auction cases of ancient sculptural art:

1. Hamilton Aphrodite (Roman marble sculpture)

This Roman Imperial–period statue of the goddess of love was sold at Sotheby’s London in 2021 for approximately USD 24.6 million (about £18.6 million), becoming the highest recorded auction price for an ancient marble sculpture.

2. Artemis and the Stag (bronze sculpture)

This early Roman or Hellenistic bronze sculpture was sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2007 for approximately USD 28.6 million, once holding the auction record for ancient sculpture.

3. Other notable auction results for ancient Roman portrait sculptures

Available data indicate that some Roman marble busts have approached the ten-million-dollar level at major auctions (for example, a portrait of a Roman emperor sold for approximately USD 7,362,500 in a 2007 auction).

Note: While the overall highest auction prices are often held by modern and contemporary sculptures—such as works by Giacometti or Brâncuși—the ancient Roman sculptures listed above still represent extremely high benchmarks within the category of antique sculpture. Beyond these headline results, many ancient Roman sculptures sold at general antiquities auctions typically achieve prices ranging from tens of thousands to several hundred thousand dollars, depending on subject matter, condition, size, and historical significance.

Below, we analyze the advantages and disadvantages of collecting ancient sculpture, along with categories and grading, methods of preservation, legal purchasing channels, and key considerations, in the hope of assisting collectors interested in this field.

Key Focus Areas in Collecting Ancient Sculptural Art

1. Combined historical and cultural value

Classical sculpture is not merely an aesthetic expression but a witness to civilization. Whether Roman deities or imperial portraits, such works directly reflect the core religious, political, and social concepts of their time. Authentic pieces possess not only artistic value but also serve as windows into historical understanding.

2. Independence as an asset class

Compared with assets such as stocks or real estate, high-quality sculpture often demonstrates greater stability during market fluctuations. The scarcity of cultural assets means that truly significant works tend to lose value more slowly over time—provided their provenance is clear and their condition well preserved, they can be held and passed down over the long term.

3. A wide range of collecting levels

Collecting ancient sculpture is not limited to a small number of “headline” masterpieces. Small Roman busts, Hellenistic portraits, funerary reliefs, and ritual sculptures can all serve as points of entry into collecting.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Collecting Ancient Sculpture

Advantages:

• Deep cultural accumulation: A single sculpture often carries information about its era, religious meaning, or political symbolism.

• Strong scarcity: The passage of time continually reduces the number of well-preserved ancient objects in existence.

• Strong intergenerational appeal: Sculptures by renowned hands or from major historical periods are frequently sought after by museums and prominent collectors.

Disadvantages:

• High difficulty of authentication: Ancient sculpture includes many copies, restorations, and even forgeries; authentication requires an exceptionally high level of expertise.

• Legal and ownership risks: Many countries enforce strict regulations on the export and trade of antiquities; unclear provenance can result in confiscation.

• High conservation costs: Stone and bronze sculptures require different conservation approaches, and improper storage can cause irreversible damage.

Collectible Categories and Reference Grading

Commonly used grading and reference categories for ancient sculpture in the collecting world include:

Grade A: Top-tier masterworks or historically central pieces

• Includes works by important sculptural masters, objects witnessing major wars or political turning points, and complete large-scale statues.

• Transaction prices often exceed one million USD.

Grade B: Portraits of historically significant figures or large stone sculptures

• Roman imperial busts and works depicting major historical figures.

• Market prices generally range from hundreds of thousands to one million USD.

Grade C: Typical antiquities and thematic sculptural works

• Small statues, decorative objects, sarcophagus reliefs.

• Prices range from tens of thousands to over one hundred thousand USD.

Grade D: More commonly circulating antiquities

• Common Roman sculptural fragments or partial funerary carvings.

• Market prices may range from several thousand to tens of thousands of USD.

These grades reflect both art-historical significance and market transaction data.

Preservation Methods and Practical Considerations

1. Environmental control

• Stone sculptures (such as marble and granite): Avoid humidity, acidic gases, and direct strong light; maintain stable temperature and humidity.

• Bronze sculptures: Prevent exposure to salts and excessive humidity, which can cause bronze corrosion.

2. Professional cleaning and restoration

Do not use household cleaners to wipe old sculptures. Engage professional conservators to address surface dust and damage, avoiding harm to stone texture or metal patina.

3. Documentation and archives

Establish a professional archive including provenance documentation, authentication reports, conservation records, and photographs, which aids future valuation and transactions.

Legal Channels for Purchasing Ancient Sculpture

1. Internationally renowned auction houses

• Sotheby’s

• Christie’s

• Phillips

These institutions maintain regular antiquities auction calendars worldwide and provide expert authentication and risk control.

2. Specialized antiquities and cultural heritage fairs

International fairs such as TEFAF Maastricht and the NYC Antiquities Shows offer opportunities to view works in person and build professional networks.

3. Specialized antiquities dealers and private channels

Long-established and reputable dealers can provide provenance chains and professional support, but legality and origin must always be verified.

Key Considerations When Collecting Ancient Sculpture

1. Legitimate provenance as a priority

Ensure the work is free from wartime looting or illegal export issues, as these involve international legal risks.

2. Professional authentication is essential

Whether before or after purchase, detailed reports from qualified experts or institutions should be obtained.

3. Maintain a complete documentation chain

Contracts, photographs, transport records, and conservation documentation should all be preserved.

4. Avoid speculative price chasing

Collecting should prioritize cultural value and personal appreciation rather than short-term price fluctuations.

5. Adopt a long-term perspective

The investment return cycle for antiquities is far longer than that of modern art and is not suited to short-term trading strategies.

Why Do We Still Need These Sculptures Today?

When we stand before ancient Roman sculpture today, we are not merely “appreciating antiques,” but confronting a way of thinking that once shaped the world. Rome no longer exists, yet through sculpture it projected its order, ambition, and rationality into time. Sculpture gives history weight and allows memory to exist beyond written records.

For this reason, ancient Roman sculpture belongs not only to museums, but to the history of civilization itself. They are not static objects, but witnesses that continue to speak. Collecting ancient sculpture is both a cultural pursuit and a dialogue with history. It demands patience, expertise, and respect. Truly exceptional works—whether Roman Imperial busts or sculptures embodying mythological power—not only preserve value in the market, but also offer collectors a unique resonance in aesthetic experience and civilizational memory.

Comments