More Dangerous Than the Loss of Cultural Relics Is Institutional Imbalance — A Public Reflection on the Disorder within China’s Collecting World

- OGP

- Jan 22

- 14 min read

By OGP Reporters / Images used in this report are sourced from publicly available materials and member archives, strictly for public-interest reporting and scholarly discussion

Oh Good Party

Our generation may not be able to change the system overnight, but we can at least refuse to be silent witnesses, leave verifiable memories for our predecessors, and ensure that future generations have clues with which to ask questions. The meaning of collecting has never been possession. Having come this far, we often ask ourselves: what is collecting ultimately for? The end of collecting is not liquidation, but the survival of civilization. If one day our collections must leave our hands, they should depart with dignity—entering the public realm, not the black market. This time, many silent collectors have chosen to speak. Not because of the high price of a single painting, but because of fear—the fear that one day we may hand over our most precious possessions, only to discover they have been quietly removed in the absence of witnesses.

A Fracture of Trust: How a Single Scroll, Spring in Jiangnan, Triggered Suspicions of Cultural Relic Loss at the Nanjing Museum

The Nanjing Museum is one of China’s first group of “National Grade-One Museums,” standing alongside the Palace Museum in Beijing and the Shanghai Museum as one of the three major pillars of China’s cultural heritage system. It houses the core legacy of Jiangnan culture and once bore the responsibility of safeguarding cultural relics relocated south from the Palace Museum during the War of Resistance against Japan. For decades, it has been regarded as a critical “vault” of national memory.

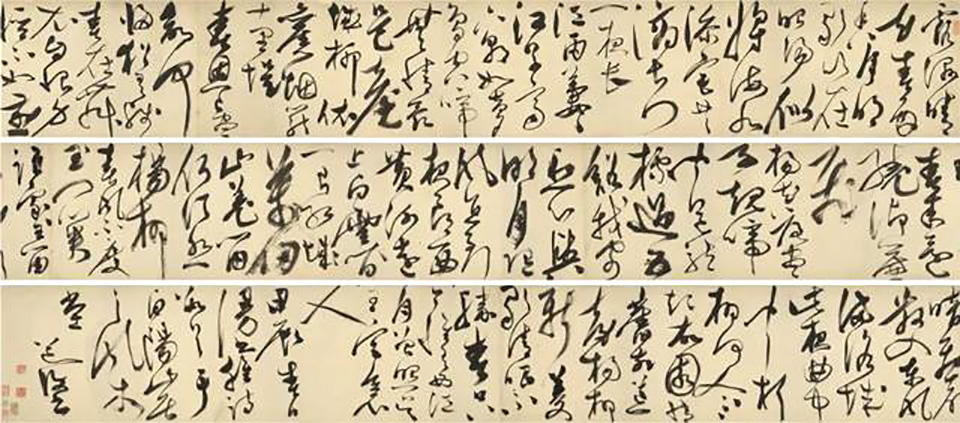

Yet at the end of 2025, an auction-related controversy surrounding the Ming dynasty painter Qiu Ying’s handscroll Spring in Jiangnan abruptly placed this century-old institution at the center of a profound crisis of trust.

Around December 26, 2025, China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration and the Jiangsu Provincial Party Committee announced the launch of investigations into suspicions of “internal theft” of cultural relics at the Nanjing Museum. Multiple media outlets reported that the museum’s former director, Xu Huping, had been taken in for questioning. The trigger was a handscroll donated in 1959 by the family of the collector Pang Lai-chen, which suddenly appeared in May 2025 at the preview exhibition of China Guardian Auctions in Beijing, carrying an estimated value of 88 million RMB. According to Nanjing Museum archives, however, this painting had already been identified as a “forgery” in the 1960s and was formally “removed from the collection” in 1997.

In 2001, an unidentified “customer” purchased the work for 6,800 RMB. The sales receipt described it as “an imitation landscape scroll in the style of Qiu Ying.” This transaction has since become the most questionable link in the entire case: Why was the buyer anonymous? Why was the price far below market levels even at that time? And who authorized the removal of a state-owned museum object from the collection?

Upon discovering the matter, Pang Shuling, a descendant of the Pang family, reported it to the national cultural heritage authorities, leading to the emergency withdrawal of the auction lot. In December, multiple individuals claiming to be employees of the Nanjing Museum filed real-name reports against Xu Huping, alleging that during his tenure he had “reclassified large numbers of cultural relics relocated from the Palace Museum as forgeries and then resold them.” Public opinion escalated rapidly, prompting official intervention.

From 6,800 RMB to 88 million RMB, the price difference exceeds ten thousandfold; from “forgery” to auction centerpiece, the object’s status underwent a complete reversal. This is not merely theatrical volatility in the art market—it strikes at the most fundamental red line of public museums: Who has the authority to decide the life or death of a cultural relic? How is the will of donors respected? And how can state-owned collections flow into private hands?

Image of “Spring in Jiangnan” attributed to Qiu Ying, shown here for news reporting and academic commentary purposes. Source: publicly available online materials.

I. Why “Using Public Instruments for Private Gain” Is Especially Lethal in the Cultural Heritage Field

In every industry, corruption carries a cost. But only in the cultural heritage field does corruption amount to the murder of time itself.

Embezzled project funds can, in principle, be recovered through audits. A swapped or misappropriated cultural relic, however, may permanently silence an entire segment of history. The authority of museums and art institutions is, at its core, a form of collective entrustment—we hand over irreplaceable civilization to a very small number of custodians. When those custodians transform “the right to research” into “the power of disposal,” and turn “authentication conclusions” into “channels for monetization,” this ceases to be a mere economic crime. It becomes a betrayal of institutional credibility, an insult to collectors who devoted their lives and fortunes to preservation, and ultimately a severing of the continuity of human civilization itself.

As members of the collecting community, this is precisely what we find most intolerable—not the pursuit of profit in the market, but private desire cloaked in the authority of the public good.

For a legitimately held object to travel from a museum storeroom into the realm of capital interests, only three sentences are required:

“Identified as a forgery.”

“Removed from the collection in accordance with regulations.”

“Disposed of through adjustment.”

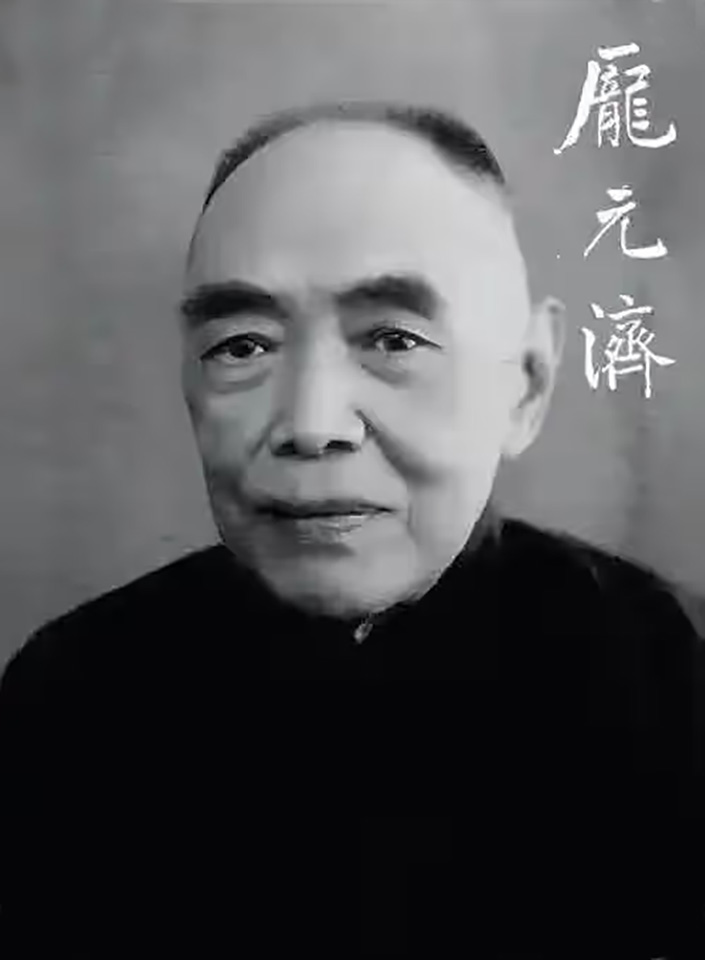

Portrait of Pang Yuanji (courtesy name Laichen), historical photograph, used here for contextual reference.

II. Why We Are So Angry

Many people do not understand: it is only a painting, only an object—why are collectors reacting with such intense emotion?

Because we understand too well the weight carried by a single cultural relic. Behind it lie generations of family guardianship, memories protected at the risk of life during times of war, and the survival of history in its struggle against time. When such an object is sold under the name of an anonymous “customer,” at an absurdly low price, what is being humiliated is not merely the object itself, but an entire cultural lifeline.

As members of a collectors’ club long active in the art market, we have also discussed the “Nanjing Museum loss of Qiu Ying’s Spring in Jiangnan handscroll incident,” and reached the following consensus:

First, the overall reliability of the Pang Lai-chen collection is exceptionally high.

During his lifetime, Pang Lai-chen maintained close relationships with figures such as Wu Hufan and Zhang Daqian. The provenance of his collection is clear, and its transmission well documented. Whether at the Palace Museum in Beijing, the National Palace Museum in Taipei, or the Shanghai Museum, works from the Pang family collection are regarded as institution-defining treasures. Against this broader context, the simple classification of multiple core calligraphy and painting works as “forgeries” is, from an academic standpoint, highly abnormal.

Second, even if deemed a “forgery,” that does not justify removal.

A fundamental ethical principle in the cultural heritage field is that donated objects are first and foremost historical testimony. A “forgery” may well be an old imitation from the Ming or Qing dynasties, and still holds significant research value. Museums do not collect only “authentic masterpieces”; they also collect “evidence.” Therefore, the Nanjing Museum’s commercialization of the work on the grounds that it was “fake” already violates basic principles of museology.

Third, the price of 6,800 RMB defies logic.

In the 1990s, sales of calligraphy and painting through cultural relic shops were generally conducted under real-name registration. Even ordinary Qing-dynasty imitations were priced far above this level. An anonymous sale under the label of “customer” would have been nearly impossible, unless there was a deliberate effort to evade traceability.

Fourth, the liability shield of auction houses.

Globally, auction houses assess the authenticity of calligraphy and painting primarily on the basis of documentation and provenance, and do not assume absolute guarantees of authenticity. That China Guardian Auctions was willing to assign an estimate of 88 million RMB indicates that a substantial degree of consensus had already formed within both academia and the market—standing in sharp contradiction to the designation of the work as a “forgery.”

What is even more chilling is that many so-called donations were not truly “voluntary.”

Taking the “Nanjing Museum loss of Qiu Ying’s Spring in Jiangnan handscroll incident” as an example:

The Nanjing Museum was established in 1933 under the advocacy of Cai Yuanpei as China’s first modern museum, then known as the National Central Museum. At the time, its capabilities in connoisseurship, cataloguing, conservation, restoration, and even transportation of cultural relics ranked first in the nation, unmatched in its era.

The Pang family of Nanxun was at that time one of the “Four Great Houses.” Their ancestors had, together with the famed comprador Hu Xueyan, provided military funds to Zuo Zongtang, and later formed marital alliances with the Zhang family, also one of the “Four Great Houses.” Both families were financial supporters of Sun Yat-sen and later backed Chiang Kai-shek during his rise to power, exerting enormous influence on modern Chinese history. Among them, Pang Yuanji (1864–1949), courtesy name Lai-chen, is widely recognized as one of the most important Jiangnan collectors of the late Qing and Republican periods. He was highly accomplished in calligraphy and painting, ceramics, and bronzes, and his “Xuzhai” collection occupies an exalted position in modern art history.

Collecting requires not only wealth, but knowledge and discernment. As the saying goes in the trade: “Three to five years for ceramics, ten years for calligraphy and painting.” Authentication of calligraphy and painting is extraordinarily difficult and prone to error, yet these works represent the highest tier of collecting. For example, when Puyi left the Forbidden City in 1924, most of what he took with him were calligraphy and paintings. Ceramics, however exquisite, were still regarded by the aristocracy as mere objects, whereas calligraphy and painting embodied the spiritual will of the literati.

Unlike Zhang Boju — one of the four great young masters of the Republican era — who favored collecting singular, unmatched masterpieces, the Pang family’s collection followed a clear and systematic lineage. Pang Yuanji’s collecting spanned the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, representing a truly ordered transmission. Beginning with Zhan Ziqian’s Spring Outing from the Sui dynasty, the collection included Dong Yuan (Tang), the monk Juran (Tang), Huang Gongwang (Yuan), Wang Mian (Yuan), Ni Zan (Yuan), Qian Xuan (Yuan), Shen Zhou (Ming), Wen Zhengming (Ming), Tang Bohu (Ming), Qiu Ying (Ming), Wu Li (Qing), and many others.

Pang Yuanji passed away in 1949, but amid the chaos of war and political upheaval, the Pang matriarch refused to relocate to Taiwan, and the family remained on the mainland. What followed were “public–private partnerships,” the Anti-Rightist Movement, and the Cultural Revolution. As the saying goes, “a man is innocent, but his jade is guilty.” The Pang family was immensely wealthy, with countless rare treasures—who would not covet them? As early as 1953, Zheng Zhenduo, then director of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, had set his sights on the Pang collection, declaring that it “ought to belong to the state.” In 1958 and 1959, repeated pressure was applied to “hand it over to the state.” Forced by circumstances, the Pang family had no choice but to “donate” their treasured collection—truly a case of “wealth that cannot be relinquished.” In January 1959, Pang Zenghe, a grandson of Pang Yuanji, handed over 137 calligraphy and painting works to the Nanjing Museum.

According to the Nanjing Museum’s “statement of circumstances,” an expert panel consisting of Zhang Heng, Han Shenxian, and Xie Zhiliu identified five disputed paintings as “forgeries” in 1961. In 1964, they were again identified as “fake” by another group including Wang Dunhua, Xu Yunqiu, and Xu Xinnong. The first three are universally acknowledged masters of calligraphy and painting authentication, but the professional credentials of the latter two have long been disputed, with Pang family descendants questioning whether they were “professional authenticators” at all.

However, the Pang family’s donations extended far beyond these 137 works. The Shanghai Museum also received donations from the Pang family. Subsequently, the Nanjing Museum, under the pretext of “borrowing paintings for exhibition,” borrowed several additional works and never returned them. It is easy to imagine that any museum holding the Pang collection could legitimately regard it as its core treasure. Within the field, the mere presence of Pang Yuanji’s seal is often sufficient to confirm authenticity. In 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, three truckloads of the Pang family’s calligraphy and paintings were confiscated. Very few were ever recovered afterward—many were destroyed, lost, or taken by individuals. Many officials later dismissed this as a “historical legacy issue,” but had the Pang family gone to Taiwan at the time, at the very least so many peerless masterpieces would not have simply “vanished without a trace.”

Image of “Spring in Jiangnan” attributed to Qiu Ying, and Pang Laichen's seals, shown here for news reporting and academic commentary purposes. Source: publicly available online materials.

III. Respect for Donors: The Collapse of a Core Ethical Principle Reveals a Systemic Breakdown

Even today, collectors employ protective mechanisms such as trusts and foundations to safeguard their private property, yet at certain moments these structures can still prove fragile and ineffective.

We have lived through situations where policies changed overnight, property rights were reinterpreted, and institutional promises evaporated with personnel changes. Thus emerges a distinctly Chinese tragedy: private rights are never fully recognized, while public power lacks a stable ethical foundation. This is not an isolated case. Under the banners of “organizing exhibitions” or “protection,” works are acquired at low prices; under the name of “donation,” control is centralized. The final outcome is that large numbers of works—and their records—simply evaporate. The life’s work of many masters disappears into the space between storage rooms and personal relationships, leaving no trace.

What makes this entire incident most heartbreaking is the disregard shown toward the will of the donors.

For many years, Pang Shuling repeatedly requested access to relevant records, only to be denied until partial disclosure was compelled by court intervention. Such a closed and defensive posture stands in stark contradiction to the mission of a public institution. The level of a nation’s civilization is often revealed in how it treats its donors. If even the most basic respect cannot be guaranteed, who in the future would dare entrust a lifetime of collecting to a public institution?

This controversy has exposed three major structural problems:

1. The Risk of Overlapping Identities

At the time, Xu Huping, as director of the Nanjing Museum, concurrently served as the legal representative of the Jiangsu Provincial Cultural Relics Company, creating a closed loop of interests in which one “acts as both referee and player.”

Supplementary explanation: The actual purchaser was later identified as Lu Ting, the owner of Yilan Studio. After Lu Ting’s death, no will was left behind, and his children entered into a dispute over the inheritance. They decided to consign this signature shop treasure—the Ming-dynasty Qiu Ying Spring in Jiangnan handscroll—to auction for liquidation. The auction house assigned an estimate of 88 million RMB, with an expected hammer price exceeding 100 million. In May 2025, Pang Shuling discovered the work during the auction preview and immediately reported it to the national cultural heritage authorities, prompting the auction house to withdraw the lot.

Under such circumstances, it is impossible not to suspect the following scenario: exploiting legal loopholes, the museum deliberately authenticated the work as a “forgery,” transferred it to a cultural relics shop for sale, where it was purchased at a low price by a designated accomplice, and later sold at a high price through an auction house, with the proceeds shared among the participants.

2. Loss of Control in the Deaccessioning Mechanism

The 1986 Measures for the Administration of Museum Collections was originally intended as an academic adjustment tool, a temporary measure to address insufficient operational funding for museums at the time. It has since been repurposed for commercial circulation, lacking third-party oversight.

With reference to the Interim Measures for the Management of the Withdrawal of State-Owned Cultural Relics from Collections and the Museum Registration Measures, once donated objects enter a museum’s collection, the museum does indeed possess the authority to manage them. However, the five ancient paintings identified as “forgeries” were: Qiu Ying’s Spring in Jiangnan handscroll, Zhao Guangfu’s Twin Horses Hanging Scroll, Wang Fu’s Pine Wind and Monastery Hanging Scroll, Wang Shimin’s Landscape in the Style of Northern Yuan Hanging Scroll, and Tang Yifen’s Polychrome Landscape Hanging Scroll. Among these five so-called “forgeries,” the Song-dynasty Twin Horses Hanging Scroll by Zhao Guangfu appeared at the Shanghai Jiatai Auction in 2014, where it sold for 2.3 million RMB. The seals “Pang Yuanji Seal (white)” and “Lai-chen’s Visual Blessing (red)” clearly attest to its origin as a Pang family donation. Is this not a case of insiders stealing from their own charge? And it is certainly not an isolated incident—such cases exist in many museums across different regions.

3. The Power-Driven Nature of Authentication and the Blurring of True and False

More than one hundred thousand former Palace Museum objects remain in Nanjing. Their security is not merely a local issue, but one of national cultural sovereignty—especially given that authenticity assessment of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting is inherently difficult. Works were often produced through master–apprentice delegation or workshop collaboration; original contracts and eyewitness documentation are lacking; material dating cannot be precisely attributed to an individual; and artists’ styles vary widely across different periods and states of mind. Moreover, the academic credentials and circumstances of the authenticators themselves are significant variables, as enormous are involved.

For this reason, the academic community has long reached a consensus: authentication is a matter of probability, not a judicial verdict. Even national-treasure-level works in the Palace Museum cannot be claimed as “absolutely authentic.” Under such conditions, equating authentication conclusions directly with disposal decisions is inherently risky. Even more alarming is “power-driven authentication”: when the authenticator simultaneously holds administrative authority over disposal, authenticity can easily become a tool of interest. The 2025 Spring in Jiangnan incident precisely exposes this systemic flaw, just as the 2008 Jade Burial Suit loan fraud involving 500 million RMB did before it.

Jade burial suit, Han dynasty, image used for comparative cultural discussion.

IV. The Real Structural Problem: Ensuring That “Disappearance” Is Never So Complete

Who watches the watchers?

What we are confronting is not a problem of a few individuals, but a dangerous system:

Authentication power merged with disposal power — whoever decides, can monetize.

Information monopoly — archives are not made public, authenticity cannot be debated.

Donors stripped of agency — once handed over, there is no right to question.

Market laundering channels — auctions and exhibitions become résumé-making machines.

If museums are to regain public trust, at a minimum the following are required:

a clear legal red line prohibiting the commercialization of all donated objects in perpetuity;

a complete separation between authentication and disposal;

a publicly accessible, traceable ledger of collection transfers;

and participatory oversight rights for donors’ descendants.

A museum is not a vault for power, but a contract of trust. If even the life’s work of donors can be casually erased, the harm extends beyond families like the Pang lineage—it strikes at society’s collective reverence for the preservation of history and culture.

At the same time, we want to make the solutions extremely concrete, offering every collector tools they can actually hold in their hands.

1. The “Triple Irrefutable Proof” Before Donation

Before making any donation, every collector must complete the following:

• High-resolution visual archives: multispectral imaging, details, mounting, and restoration traces

• Third-party documentation: at least two independent academic institutions

• Conditional legal clauses:

◦ permanent prohibition of commercial disposal

◦ any deaccession subject to consent from family members and third parties

◦ rights to public display and public inquiry

This should become an industry-wide consensus, not a personal choice.

2. Civilian “Parallel Archives”

Established by collector communities, including:

• oral histories

• physical-object imaging

• exhibition and circulation records

• witness registries

Even if official archives are altered, another system of memory remains for cross-verification.

We fully support collectors in becoming nodes of social memory.

3. Decentralized Authentication Mechanisms

We advocate three non-negotiable principles:

• absolute separation between authenticators and disposers

• lifetime freeze clauses for major donated works

• mandatory cross-institutional review for disputed objects

4. Ethical Constraints on Auction Houses

• explicit refusal to accept works “deaccessioned from public institutions”

• establishment of blacklists and provenance disclosure requirements

• joint liability for suspicious lots

5. Advice for Living Artists

• establish a “lifetime catalogue” for major works

• record oral accounts of creation

• designate trusted civilian witnesses

• do not entrust everything to a single institution

Image of “Spring in Jiangnan” attributed to Qiu Ying, shown here for news reporting and academic commentary purposes. Source: publicly available online materials.

VI. A Letter to Fellow Collectors

As collectors, we are usually a quiet group. Most of the time, we prefer to talk about ink tones on paper, patina on porcelain, and the lineage of provenance—rather than power and right or wrong.

Our generation may not be able to change the system overnight, but we can at least refuse to be silent witnesses, leave verifiable memories for our predecessors, and ensure that future generations have clues with which to ask questions. The meaning of collecting has never been possession. Having come this far, we often ask ourselves: what is collecting ultimately for? The end of collecting is not liquidation, but the survival of civilization. If one day our collections must leave our hands, they should depart with dignity—entering the public realm, not the black market.

This time, many silent collectors have chosen to speak. Not because of the high price of a single painting, but because of fear—the fear that one day we may hand over our most precious possessions, only to discover they have been quietly removed in the absence of witnesses.

More fragile than cultural relics is trust; more fragile than trust is memory. When public instruments are corroded by private desire, the only resistance is documentation, voice, and connection. Let us at least ensure this: that “disappearance” is never so complete, and that time itself may still testify for those who come after us.

*Images included in this report are used solely for public-interest reporting, academic discussion, and fair use purposes. No commercial use is intended.

Comments